1939. San Francisco's Japantown district

Willie Ito was 5 years old when he was taken to a neighborhood theater to see Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). He had seen cartoons before, though typically as black and white silent reels. “To see a feature-length animated film on the big screen in living Technicolor just blew me away,” Ito explains. “That was when I really felt that this was what I wanted to be.”

The young Ito soon acquired a special keepsake: a Crown Toy Company coin bank themed to the character Dopey.

Two years later, Ito found himself enjoying a December weekend in Santa Cruz with his uncle and aunt-to-be. As the fog rolled in that Sunday afternoon, they drove home to San Francisco. Approaching the city limits, “There were armed soldiers stopping some of the cars,” as Ito remembers. The United States had been attacked at Pearl Harbor by the Empire of Japan that morning.

“They were only stopping Asians,” Ito continues. His uncle was able to provide identification, and once in the city, “Every corner had a newspaper boy shouting, ‘Extra! Extra! War!’ I had never heard the word ‘war’ before. But I soon found out what it meant.”

Ito’s family, like all those in Japantown, had gathered in their homes. “Everyone worried, ‘What’s going to happen to us?’” Ito’s parents were American-born. His maternal grandparents were native Japanese.

Soon after the declaration of war, “the FBI came around to our homes to confiscate anything that was deemed contraband, including weapons—our family lost our heirloom sword, or katana—and even books printed in Japanese.”

One day after school, Ito arrived home to find the agents searching the place, all wearing trench coats and caps “like Humphrey Bogart.” Once they’d left, Ito quickly ran upstairs, afraid his prized Dopey bank had been taken, but thankfully, it was still there.

Air raids and blackouts were in effect. Rumors spread of forced removal, or worse. In February of 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 ordering the “evacuation” of all Japanese-American citizens living on the west coast.

Soon, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt implemented the orders from his office at San Francisco’s Presidio to begin the process of “relocating” thousands of Japanese-American citizens in the San Francisco Bay Area.

“When we were evacuated,” Ito explains, “you could only take what you could carry. My parents kept to what was necessary, so the Dopey bank didn’t come along.” The Ito family was soon staying at Tanforan Racetrack just south of San Francisco, where some had been made to sleep in horse stables.

“My father was optimistic and figured that we would be returning to our home. But many in the community figured that was it.” Some sold their homes, cars, or other property. But the Itos rented their house on Bush Street to a friendly Chinese family who would keep the place in order until the war ended.

He lost everything with the war. He finally died in camp. I guess it was from heartbreak.

The Ito family was bound for incarceration at Topaz, deep in the Utah desert. It was the autumn of 1942. Willie Ito was 8 years old.

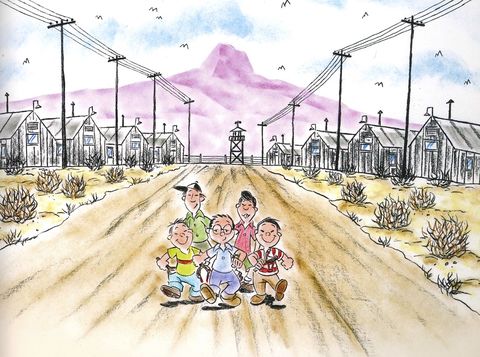

Some 150 miles south of Salt Lake City, the Topaz camp was home to over 8,000 American citizens. They lived in barracks that were usually uninsulated and heated by coal stoves. Snow fell as early as October.

For many of the children, incarceration was “like a summer camp” as Ito explains. “We didn’t realize how horrendous the experience was for our parents and grandparents. They never really wanted to discuss it in front of us.”

Ito’s immigrant grandfather had worked hard to build a business, home, and family in San Francisco. “He lost everything with the war,” says Ito. “He finally died in camp. I guess it was from heartbreak.”

Everything from clothing to household goods had to be mail-ordered from the Sears & Roebuck or Montgomery Ward catalogs. “I would get the expired catalogs afterwards,” says Ito, “and in the corners I’d make little drawings. Those flip books were my first foray into the art of animation.”

When not occupied in school, drawing was Ito’s prime source of entertainment. “I’m not a jock,” as he adds. For the young boy in camp, a private tragedy was to miss the weekly delivery of the San Francisco Chronicle with its color Sunday comics. “So I just drew my own,” he says.

Lo and behold, the camp’s own Topaz Times—a self-published newspaper—featured a standout cartoonist who had already worked in animation at the Walt Disney Studios: Bennie Nobori.

Nabori’s in-camp comic strip, “Jankee,” had a bold, playful style. “When I saw that it blew me away,” Ito remembers. “Here was a comic strip done by a fellow Japanese-American kid. It was all done for us. I became a voracious follower of ‘Jankee.’”

Ito never met his early cartoon hero, but the impact was enough to hold him to his art. The camp at Topaz in particular fostered an active group of Japanese-American painters, writers, intellectuals, and even activists.

Ito counts his own father in that lineup of creative talent. “Topaz is in an old salt seabed,” he explains. “If you dig in the ground you find this fossilized shell, often bleached white. My father would excavate these, color them with nail polish, and add lacquer to create a little flower with a crate paper stem. He’d also weave little baskets from crate paper and make brooches.”

“When we came back in 1945, the first thing I did was run to my bedroom. The Dopey bank was still there. The only thing missing was all the pennies I had kept inside!” Ito was 11 years old.

Through adolescence, Ito witnessed many of his fellow young Japanese-Americans pursuing careers in fields like medicine, law, or the sciences. While a student at San Francisco City College, he briefly considered learning medical illustrating. An art teacher assured him that he wouldn’t enjoy it. “You want to be a cartoonist,” he told the young man. So, he referred Ito to the one school known to produce Disney animators: Chouinard Art Institute.

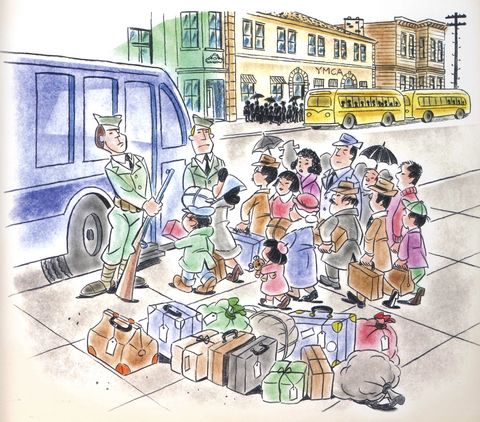

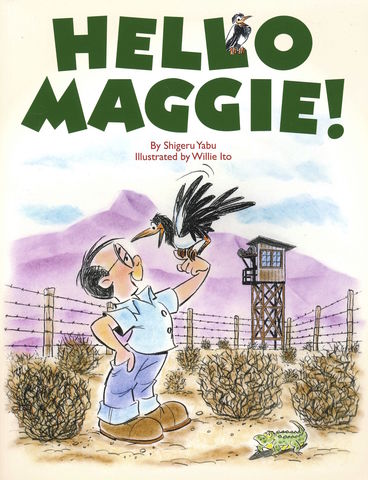

How does one reconcile this past with the present and future? For Ito today, the answer is to tell the story to children. His skills in cartooning have come full circle with Hello Maggie!, a youthful tale illustrated by Ito in his retirement and written by his childhood friend, Shigeru Yabu, who spent his war years incarcerated at Heart Mountain in Wyoming.

Hello Maggie! tells the story of a young Japanese-American boy at Heart Mountain—perhaps an amalgam of Ito and Yabu—who befriends a magpie bird known as Maggie. Saddened at losing his pets before the incarceration, the boy finds Maggie a welcome new companion, and together they romp about the camp.

“Maggie became iconic,” Ito explains. The story, which they self-published, is sold at museums where young visitors can discover its heart and wisdom. “My grandkids can now read this.”

This article is part one of a two-part article about the incredible story of Willie Ito.

Part II—"'I Just Wanted to See the Place': Willie Ito at The Walt Disney Studios"—can be found here.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image credits (listed in order of appearance):

- Willie Ito, 2019; photo by Lucas O. Seastrom; Mickey Mouse © Disney

- Hello Maggie!; courtesy of Yabitoon Books

- Hello Maggie!; courtesy of Yabitoon Books

- Hello Maggie!; courtesy of Yabitoon Books

- Willie Ito, 2019; photo by Lucas O. Seastrom; Mickey Mouse © Disney

- Hello Maggie!; courtesy of Yabitoon Books