Walt Disney featured the ancient Greek god Apollo in his 1940 animated feature Fantasia. At the conclusion of Beethoven’s “The Pastoral Symphony,” a violent storm clears, and mighty Apollo is seen aboard his chariot illuminated before the setting sun. In another Fantasia sequence, Igor Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring,” Disney artists portrayed an astounding view of the cosmos, pushing through galaxies and starfields to the Earth itself, a view no human had yet glimpsed in reality.

Disney Turns to Space

In the early decades of his career, Walt Disney used film and animation to bring fantasies to the screen. By the mid-1950s, he had turned his sights on a new medium, television, and put his artists to work on an array of diverse projects.

When the Disneyland television series premiered in October 1954, it promised stories and programs from four distinct lands in the still-under-construction theme park: Fantasyland, Adventureland, Frontierland, and Tomorrowland. With no existing library of material to populate the Tomorrowland segments, Walt assigned a team, directed by veteran animator Ward Kimball, to develop “science-factual” programs about the possibilities of human space exploration, among other topics.

“There are two sides to go on this—comedy interest and factual interest,” Walt himself would note in an early story meeting in April 1954. “Both of them are vital to keep the show from becoming dry… We want to do something new on our show… We are trying to show man’s dreams of the future and what he has learned from the past.”

Just a month later, Walt added in another conference, “We are known for fantasy, but with these same tools that we use here we apply it to the facts and give it a presentation. I think that’s very important for this series—a science-factual presentation.”

Tomorrowland Features Space Programs

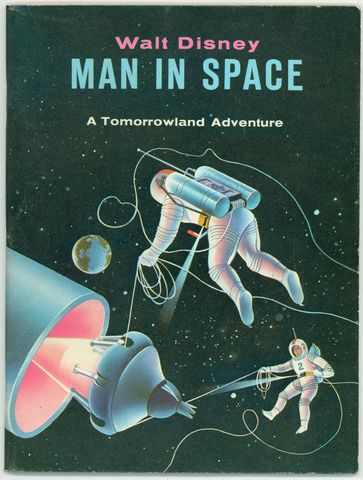

Three one-hour Tomorrowland programs were ultimately made on space: “Man in Space” (1955), “Man and the Moon” (1955), and “Mars and Beyond” (1957). Leading German scientists, repatriated after World War II for American aerospace development, were recruited as consultants and hosts on the programs. These included Wernher von Braun, Willy Ley, and Heinz Haber.

Wernher von Braun had already started boosting the promise of space travel to the American public. As Ward Kimball later recounted to historian Rick Shale in 1976, “He was having a hard time convincing the brass that we should be building rockets... So he looked upon Disney’s as a marvelous outlet for his ideas. He’d been writing in Collier’s, but that reached just a small segment of the people. He realized also that our television show had a big audience.”

Scientists + Disney = Talented Storytelling

The scientists’ expertise meshed with the Disney team’s penchant for storytelling. Concepts such as rocketry, the absence of gravity, and an orbital space station were presented with a blend of live-action and animation in a pseudo-documentary style.

“Man and the Moon” was especially prophetic. Disney used animation to depict a caricatured history of human civilization’s relationship with the Moon. Live-action was used for Kimball and von Braun’s explanations of scientific principles, as well as a dramatic portrayal of a future manned orbit around the Moon, not unlike the Apollo 8 mission years later in December 1968.

The Soviet Union’s Sputnik satellite wouldn’t launch until the fall of 1957, and the preceding release of the first Disney programs captured the uninitiated imagination of American audiences, including those in positions of influence. It’s often recounted that President Eisenhower requested "Man in Space" to be screened at the Pentagon as, in Ward Kimball’s words, “an education space primer.”

The Beginning of the Space Race

With Sputnik circling overhead, the space race commenced, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was formed in 1958, along with the National Aeronautics and Space Council, chaired by the President.

On April 12, 1961, the race accelerated when the Soviet Union launched cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin beyond Earth’s atmosphere. President John F. Kennedy appointed Vice President Lyndon Johnson as chairman of the National Aeronautics and Space Council.

Johnson consulted Wernher von Braun regarding the United States’ then-present capabilities to outpace the Soviets. The former Disney collaborator—by now, director of the Marshall Space Flight Center—told the Vice President that the United States was not making a “maximum effort” in its space program, but if that would change, “we have an excellent chance of beating the Soviets to the first landing of a crew on the Moon.”

Wernher von Braun was sticking to his guns in the literal sense. An “all-out crash program” could develop a rocket system capable of reaching lunar orbit and even manned landings. The program had been dubbed “Apollo” by NASA Director Dr. Abe Silverstein, who explained that the image of “Apollo riding his chariot across the Sun was appropriate to the grand scale of the proposed program.” Mythological names had become the norm for space-related initiatives and programs.

Disney, Space, and the Space Flight Center

In 1965, Walt Disney received an invitation from von Braun to visit the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama where elements of the Apollo program were in active development. Roy Disney, among others, joined Walt there in April.

As NASA historian Mike Wright notes, “von Braun and his employees clearly hoped that the reunion might rekindle Disney's enthusiasm for space exploration.” Walt himself told a local reporter during his visit that “If I can help through my TV shows... to wake people up to the fact that we've got to keep exploring, I'll do it."

Disney Space Films and Their Impact

Walt’s death in 1966, when Apollo 1 was still in preparation, seemed to have ended hopes for new Disney films on spaceflight. He’d seen humans reach space, but would miss the triumphs of the Apollo program. Nonetheless, the Tomorrowland shows and the land itself at Disneyland had made their mark on the American psyche.

Ward Kimball and the artists involved remained proud of the relative technical accuracy of the 1950s programs. When astronauts first orbited the moon on the Apollo 8 mission, Kimball received a phone call from his old collaborator Wernher von Braun. “Well Wahd,” von Braun told him with a heavy accent, “they’re following our script.”

The live television broadcast of the Apollo 11 moon landing was screened on stage in Tomorrowland for Disneyland guests on July 20, 1969 (both Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin would later visit Disneyland). Hundreds watched where nearby a 1955 attraction, Flight to the Moon (originally entitled Rocket to the Moon), still offered visitors a fantastic glimpse of what was becoming reality before their eyes.

The Apollo 11 moon landing, and the entire American space program, has realized the dreams of storytellers like Walt Disney and scientists like Wernher von Braun. The original space race was also a strong political statement by the United States to the world’s nations, and one in particular. But it was dreamers like Walt who reminded us that voyages into space could also be cooperative adventures shared across borders and made in the spirit of peace.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image credits (listed in order of appearance):

-

Bill Bosché, Walt Disney, and Ward Kimball, 1957; Walt Disney Family Foundation, collection of Ward Kimball; © Disney

-

Man in Space book, 1959; Walt Disney Family Foundation, collection of Ward Kimball; © Disney