In recent decades, many children of Walt Disney’s close collaborators have shared cherished memories of growing up at The Walt Disney Studios, wandering the hallways of the Animation Building, and exploring the backlot and soundstages. Others recall the halls and workshops of the WED Enterprises facilities where Audio-Animatronics® figures were brought to life for theme park attractions.

But for Laurence Boag, his dad’s workplace wasn’t the behind-the-scenes world of filmmaking and theme park design. It was a small stage inside Disneyland’s Golden Horseshoe saloon, where the venue’s celebrated Golden Horseshoe Revue delighted park guests for more than 30 years, becoming one of the longest-running stage shows in history.

At the heart of the Revue was Wally Boag, who regaled the audience with his piercing wit, mastery of language, deft sleight of hand, and hilarious physical antics. “I’m Wally Boag,” he would say to the crowd as he came onstage, “that loud, long, lean, loquacious, sometimes laconic lunatic who loves to deal, delve, and dabble into delirious dialogues and dynamic dissertations… or in other words, I’m a traveling salesman.” Performed five times a day, five days a week, Boag’s act was a masterpiece that has become iconic both for its own brilliance and its lasting impact on then would-be comedian Steve Martin, for whom Boag was an early mentor.

At one point in Boag’s act, where the comedian is posing as the wild cowboy known as Pecos Bill, he exclaims, “I’ve got the fastest draw in the West. Want to see my fast draw?” The audience eagerly cries “Yes!” While Boag remains perfectly still, arms and legs posed for a shootout, a gun is heard firing. “Want to see it again?” the performer then asks.

“I brought him that joke,” says Boag’s son, Laurence, who turned six years old when Disneyland opened in 1955. “I’d heard it as a kid and told him he ought to do it. At first, they didn’t have the gunshot backstage, but then they developed it so that the stage manager would shoot the gun back there.”

Before earning his Disneyland role at 35, Oregon native Wally Boag had spent some 20 years dancing and joking his way across vaudeville and nightclub stages to some of the most prestigious venues in the world, “even for kings and queens,” as Laurence points out. After he married actress Ellen Morgan in 1943, daughter Tracy was born in 1947, followed by Laurence two years later. The family was accustomed to a show business life on the road, living in New York, France, England, Los Angeles, and Australia—among other locales—before coming back to Los Angeles again in the mid-1950s.

Disneyland’s construction was nearly finished when the elder Boag was recommended by actor and singer Donald Novis to audition for a “soda-pop show” at the new park. Inside a soundstage on the Disney Studios lot in Burbank, along with an accompanying piano player the comedian performed for a lone audience member, Walt Disney. Boag’s act included physical slapstick, elaborate magic tricks and gags, bagpipes (dubbed the “Boag-pipes”), and balloon animals (known as “Boag-alloons”). Accustomed to performing for adult crowds at nightclubs, he famously told Walt, “I can clean it up,” as he finished the audition. Disney signed him to a two-week contract, which ultimately became a 27-year stint with The Walt Disney Company.

70 years later, Disneyland has added large-scale attractions and highly-produced, technology-infused shows. But in the park’s earliest years there were no “E”-ticket thrill rides, and live performances by groups of entertainers were an essential ingredient to Disneyland’s charm and appeal. “You didn’t need to go on attractions,” Laurence explains. “All of the live entertainment was phenomenal. You could spend hours there watching the shows and talking to people. You could just sit on the porch somewhere in the park and watch everything go by.”

The Golden Horseshoe Revue was a short-form vaudeville act served up as a family-friendly slice of the Old West. Boag was joined by tenor Donald Novis (later succeeded by Fulton Burley) and emcee Judy Marsh (likewise succeeded by Betty Taylor), a troupe of dancers, and a trio of musicians. Their first performance came four days ahead of the park’s opening, when Walt and Lillian Disney celebrated their 30th wedding anniversary at the newly-finished saloon. By the end of its run in the 1980s, the Revue’s performance count totaled over 45,000 shows, which remains in the Guinness Book of World Records.

“He was having fun,” Laurence Boag remembers about his dad. “Every day was a new audience. During Walt’s tenure at the park, he was given so much freedom. He could do prat falls in the gun fights that happened outside between Horseshoe shows, all these different things. Walt handed him projects right and left. There were things at the studio, roadshows all across the United States, radio shows, [Walt Disney’s] Enchanted Tiki Room (for which Boag voiced José), all things that he had a great time doing. There was great diversity in his opportunities.”

But the fun was not limited to the elder Boag. For Laurence, Disneyland was a second home throughout his childhood, sometimes literally in the sense that he’d often sleep over at the park in his father’s dressing room—today part of the upper floor of Frontierland’s River Belle Terrace restaurant. “I used to love to go out and walk around when the park was closed,” the younger Boag recalls. “You’d see the gum-scrapers out there with bottles of [rubbing] alcohol and razor blades. They’d sit on roller-boards and go along scraping, keeping the park clean. Others would be hosing down things. Some would be re-painting the shooting galleries and [queue] chains everywhere. They’d be tuning the engines for the Jungle Cruise boats and Autopia cars. We’d visit the horses in the stables. There were a lot more back then between the mule train, covered wagons, stagecoaches, and the streetcars on Main Street.”

Seeing Walt Disney around the park was a common occurrence, and Boag’s father was known to have an especially good rapport with the boss. “People always point that out, that Walt was never upset with Dad or defensive about things,” Laurence notes. “He was comfortable. A handful of times, he was up in Dad’s dressing room just hanging around with him.” In 1965, while celebrating Disneyland’s 10th anniversary with the park’s Cast Members, Walt made a rare gesture and publicly recognized Boag during his remarks, saying, “Wally, we’ve been very happy. We hope you’ll stay with us. I hope you’ve been happy.” The comedian drily replied, “We’re still in rehearsals, Walt,” to which Disney and the audience erupted with laughter.

As Laurence reflects, perhaps it was his father’s sincerity that so endeared him to Disney. The park in general was Walt’s happy place where he could find time to let go of the daily pressures of running a studio and have a little fun. At the heart of that was the Golden Horseshoe cast with their carefree sense of play and spontaneity.

“There was a certain amount of trust with Dad,” Laurence explains. “You got what you saw. He was the most unpretentious guy I’ve ever met. He was very playful, and he relaxed people anywhere he was. He could be at the bank, and he could disarm people so easily. Walt was kind of an old, frustrated vaudevillian in his head, and Dad epitomized that sort of era. They both came from pretty humble beginnings. I think they clicked. They were about 19 years apart in age, so Walt wasn’t quite old enough to be a father figure, more like a big brother.”

For the Boag family, Disneyland meant newfound stability. “Dad’s situation, like most actors, was pretty precarious,” Laurence says. “A job that runs for years at a time is rare, so you’re constantly looking for the next job and worried about getting older and not finding the work. So I think my parents were both really grateful for the Disney job. My mom appreciated the fact that Walt was so generous in giving Dad so many opportunities.”

Ellen Boag was an actor herself, having left home at 18 to start her career in show business. She had met Wally in 1942 while part of a Philip Barry stage production with Katharine Hepburn that happened to be in Boston, where the comedian also had a gig. Laurence describes his mother as “incredibly sophisticated compared to my father—well educated, well read, came from a fairly influential family. She brought a lot of worldliness to my Dad.

“Mom had been in a lot of plays, and she could’ve gotten more,” Laurence continues. “When we came back from Australia and Dad started at Disney, she took a role with CBS on a weekly radio show, Suspense. That really fed her appetite. She was usually the villainess and would scare the heck out of my sister and myself. She would often say that she gave up her career by having a family. Some of her friends kept working in things like soap operas, and she was envious of that. Dad’s job wasn’t nine to five. He was always involved in club dates and doing things for Disney, it made it that someone had to be home.” The Boags’ marriage lasted nearly 70 years before Wally’s passing in 2011.

Growing up, it seemed natural that Laurence would try his own hand at performing. “Dad taught me how to make the balloon animals and do magic tricks, and I’d perform for kids’ birthday parties,” he recalls. “And my dad would teach me to develop the patter, where you keep talking throughout the act. It was the most important thing, especially during magic, because it preoccupies them. It’s right out of the nightclub scene. You’re paying attention to what the magician is saying, but he’s also doing something with an object. Two jokes at the same time, one manual and one audible.”

Beginning in his teens, Laurence became a Disneyland Cast Member, starting at Merlin’s Magic Shop at 15 before moving to Tiki Tropical Traders in Adventureland at 17. At the time, many stores in the park were operated by lessees at which younger people could find employment before turning 18. “[Disney Legend and original park landscaper] Bill Evans was my mother’s first cousin,” Laurence explains, “and it was his wife that owned Tiki Tropical Traders. Walt gave the concession of allowing the store there. We would go there early in the morning. I’d meet Claire, and we’d drive her station wagon through the gate behind the berm off Harbor Boulevard, up Main Street, and into Adventureland to restock things.”

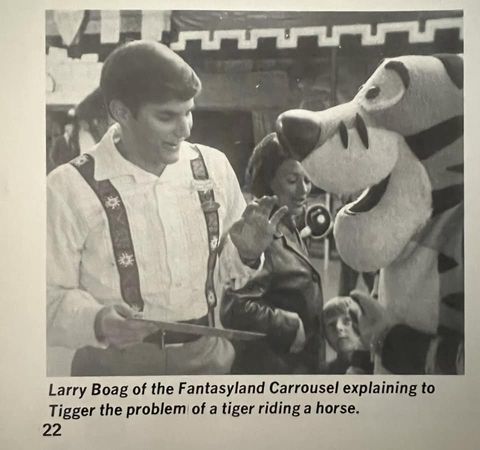

Into his early adulthood, Laurence then found roles as an official Cast Member, working everywhere from the PeopleMover and Autopia in Tomorrowland, the dark rides and King Arthur’s Carrousel in Fantasyland, and even a stint in character performing as a friend of Goofy. His favorite assignment was piloting Frontierland’s Mark Twain Riverboat on the Rivers of America. “If you worked at night during the summer, the Dixieland bands would be playing, and you’d float softly around the island,” he says. “It was heaven. I would’ve done that for free.”

Laurence’s ultimate career path would take him away from Disneyland. After serving in the Navy during the Vietnam War, he spent time in Europe. “I didn’t want to be in the States with all that was going on,” he explains. “I was really uncomfortable being a veteran. I traveled for nearly a year, working in England as a lorry driver, Germany as a house painter, Greece driving a Coca-Cola bottling truck with three wheels. Then I realized I could go to school in France, and returned to Paris to study at the Sorbonne.” Fascinated by the past, Boag studied French architectural history and worked as a tour guide in Paris. He eventually resettled in California where he taught English and French literature to high school students.

“I realized becoming a teacher, that if you’re good at it, half of what you’re doing is show business,” Laurence notes. “I was serious but also likely to make a joke every ten minutes. It was the best teaching literature to AP students, because I was so impassioned with what I was teaching. For all of us, the bell was terrible, because we were enjoying the class so much.”

In all of his adventures, Laurence is keen to note that he took Disneyland and its sensibilities with him. “They were the most formative years of my life,” he reflects, “from the time I was six until I stopped working there at 22. To this day, it stays with me. I really enjoyed myself and the people I worked with and the guests. Something else that really affected me was the detail of how it was built. One of the things that Dad and I decided to do in [the Cast Member magazine] Backstage Disneyland was to take photos of little details around the park and ask people to identify them. He sent me around with a camera and I took pictures of all these beautiful hand-made things. When I started doing woodwork for boats and things, I thought it would’ve been so much fun to do that for Disney. I’d always wanted to be an Imagineer building models. I studied art before I went into the service, and afterwards my path changed as I ended up designing and building furniture as a supplement to my teaching. Disneyland made me much more creative than I possibly would’ve been. It was such a creative place.”

After his father’s passing, Laurence eventually donated several Wally’s original props to The Walt Disney Family Museum, including the original carpet bag of tricks and gags and the “Boag-pipes.” For many years, the younger Boag enjoyed a close friendship with both Diane and Ron Miller.

“When I go to the museum, I realize that the place will keep growing and changing, as it has at the park,” Laurence concludes. “My hope is that Diane’s vision of telling the story of Walt’s life continues to be respected. That vision is very nicely expanded with the special exhibitions next door. If you really want to go to that museum, you need to go ten times and visit all the little places in the main exhibits and listen to and read everything. You really get a sense of Walt’s vision by doing that. And the museum itself is Diane’s vision, along with [former Imagineer] Bruce Gordon and everyone who worked on it.”

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (in order of appearance):

- Photograph - Golden Horseshoe Revue, with Walt Disney in the top-right balcony, c. 1955; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

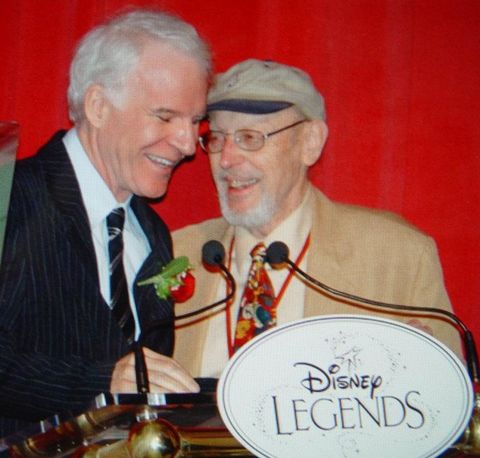

- Photograph – Steve Martin inducting Wally Boag as a Disney Legend, 1995; © Disney

- Photograph - Wally Boag performing in the Golden Horseshoe Revue; photo owned by and used with permission from Laurence Boag

- Photograph - Walt and Lillian Disney at the Golden Horseshoe sloon for their 30th wedding anniversary, 1955; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

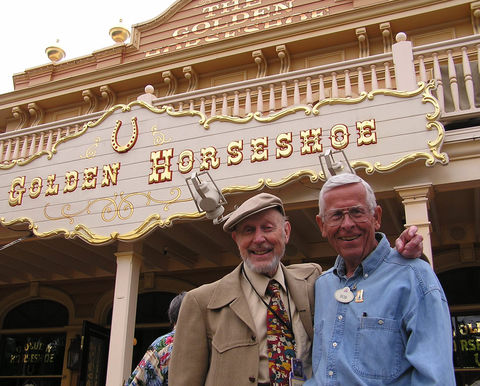

- Photograph - Wally Boag with Bob Gurr outside of the Golden Horseshoe Revue; photo owned by and used with permission of Laurence Boag

- Photograph – Wally and Ellen Boag, c. 1940s; photo owned by and used with permission of Laurence Boag

- Photograph – Laurence Boag (referenced here as Larry Boag) featured in the Cast Member magazine Backstage Disneyland; Tigger © Disney; photo owned by and used with permission of Laurence Boag

- Wally Boag's carpet bag, 1955–1982; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of the Boag Family