To highlight our new exhibition of Disney Live-action film posters in our theater lobby, we asked Disney historian, Jeff Kurtti, to give us some background on why Walt Disney moved into that genre and the success he found there.

Although popular legend has a confident and sprightly Walt Disney stepping off the train from Kansas City, Missouri in Los Angeles, with visions of a cartoon empire dancing in his head, the reality is somewhat different. “It was a big day, the day I got on that Santa Fe California Limited,” Walt admitted. “I was just free and happy you know? That was 1923.”

“But I’d failed,” he added bleakly.

His efforts to establish a movie career in the Midwest had proved unsuccessful, and he later recalled that his brother, Roy O. Disney, advised, “Look, I think you should get out of there. I don’t think you can do any more for it.”

His efforts to establish a movie career in the Midwest had proved unsuccessful, and he later recalled that his brother, Roy O. Disney, advised, “Look, I think you should get out of there. I don’t think you can do any more for it.”

Far from dreams of cartoon greatness, though, Walt admitted, “I was a little discouraged with the cartoon at that time. I felt at that time I thought I was getting into it too late. In other words, I thought the cartoon business was established in such a way that there was no chance to break into it. So, I tried to get a job in Hollywood, working in the picture business so I could learn it. I would have liked to have been a director.”

“I didn’t figure on setting the town on fire—at least not for a year or two. But I had to start with a job, for two months I tramped from one studio to another. Anything to get through those magic gates of big-time show business. But nobody bought.”

(Years later, Roy chuckled over exactly how earnest Walt’s job-hunting actually was. “I kept saying to him, ‘Aren’t you gonna get a job? Why don’t you get a job?’ He could have got a job, I’m sure, but he didn’t want a job. But he’d get into Universal, for example, on the strength of applying for a job, and then when he’d get out of the office, then he’d just hang around the studio lot all day, watching sets and what was going on. MGM was another favorite spot where he could work that gag.”)

For whatever reason—whether lack of available work, or the simple realization that working for himself was the best route—”I just didn’t get in anywhere,” Walt said, “and, before I knew it, I was back with my cartoons.”

Certainly his first cartoon series, The Alice Comedies, contained live-action sequences, and there is little doubt that Walt himself had a hand in directing them, but the focus of the shorts was its “gimmick,” that of combining animation with the live-action.

In the mid-1930s, Walt tested Technicolor photography of Mary Pickford with the idea of creating a similarly-structured feature version of Alice in Wonderland (until an ambitious 1933 live-action feature version from Paramount quashed the idea). Live-action filmmaking would remain both a strong interest of Walt’s, as well as something of a means to an end in his pictures as time went on.

Although a series of animated shorts and features had firmly fixed Walt in the public mind as “a cartoonist,” Walt never had so narrow a view of his work. He began to look at the logic of live-action again when a series of production delays on Bambi induced the quick creation of a feature for theatrical release under his distribution contract with RKO-Radio Pictures.

Ever resourceful, Walt and his team came up with a clever idea: they could leverage Walt’s fame as a Hollywood producer of cartoons, his beautiful new Burbank studio, and the public’s never-waning interest in how things are made, and create a fun, funny, energetic, and colorful “studio tour” with all-new animated sequences as the centerpieces.

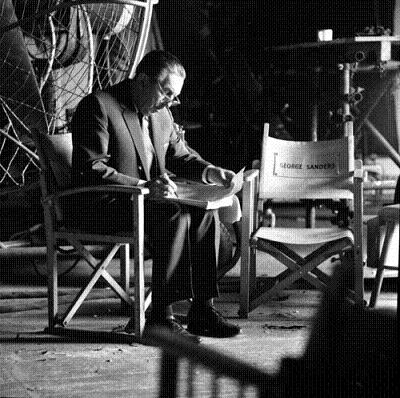

The result was The Reluctant Dragon, named for the showpiece story and animated film within the feature, and starring writer, humorist, andradio personality Robert Benchley visiting several key Disney staffers; including Ward Kimball, Fred Moore, Norman Ferguson, Clarence Nash, and Walt himself.

Although most of the film is live-action, there are several animated sequences within the “studio tour,” a segment featuring Casey, Jr. from Dumbo, Donald Duck demonstrating the animation camera and the principle of Persistence of Vision, the shorts Baby Weems and How to Ride a Horse, and the animated finale segment, The Reluctant Dragon.

Although most of the film is live-action, there are several animated sequences within the “studio tour,” a segment featuring Casey, Jr. from Dumbo, Donald Duck demonstrating the animation camera and the principle of Persistence of Vision, the shorts Baby Weems and How to Ride a Horse, and the animated finale segment, The Reluctant Dragon.

Necessity soon again compelled live-action filmmaking at The Walt Disney Studio, after the divisive 1941 Strike and the crushing effects of World War II nearly put the enterprise out of commission. “Song of the South was done during the war,” Walt recalled. “I did it during the war, and I did about thirty minutes of cartoon and filled in with a little over an hour of live action—because I couldn’t do an hour and a half of cartoon. I didn’t have enough talent.”

Pleased enough with the results of his first foray into modern live-action filmmaking, Walt planned So Dear to My Heart (adapted from Sterling North’s memoir Midnight and Jeremiah) as a live-action feature, but had animated sequences added as framing elements and to buttress story points.

“In this one I use the cartoons to support the picture,” Walt said at the time. “And by that, I mean the cartoons are used to introduce the acts. But the story is carried by the live action.”

“There was some pressure brought to bear, I’m not sure by whom,” author and film historian Leonard Maltin says, “To put some animation in So Dear To My Heart, and he reluctantly went along, I gather—not that it hurt the film at all. Those are charming sequences, but it’s essentially a live-action film. I think he got his way, and he got to make a film he cared about very deeply.”

The real beginning of a consistent attention to live-action as an ongoing part of the Studio output also came about as a result of World War II.“After the war we still had the frozen fund situation in Europe,” Walt said. “So, in order to get the funds out of England, they wanted me to go to England and do something. The first thought was could I start a cartoon studio there, and I didn’t think I could because you have to train artists for it, or else import them—and if you have to import them, it’s not helping the fund situation. I had this story Treasure Island I had wanted to do, and I suggested we go over and do Treasure Island and that way we’d use our funds.

“So making a picture over there seemed the most logical way of making use of these frozen funds. All in all, the project worked out very well, and I believe we are getting a very good picture.”

Walt was pleased enough with the results to authorize three more productions in Britain, The Adventures of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men (1952), The Sword and the Rose (1953), and Rob Roy, The Highland Rogue (1954).

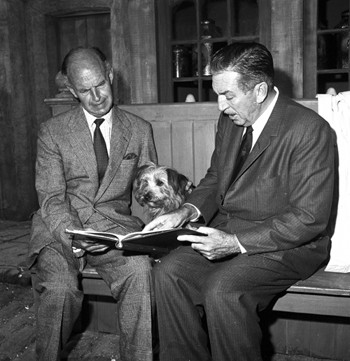

“The reason it was important was not only because he succeeded in that enterprise and created some remarkable films,” British author and Disney authority Brian Sibley says, “The films that he made in that period captured the essence of British stories.

“Walt achieved something that I’m not sure he actually knew he was going to achieve, which was that he placed himself as being not just an American filmmaker, but also a European filmmaker—or specifically a British filmmaker.

“We thought of him as making films not just about us, but making them here as well. I think that that gave Britain a kind of ‘ownership’ to Walt Disney, and that only came about in the ‘50s.”

The broadening of his film enterprises into live-action had a reciprocal and reflexive result, between the two media. “In live-action, you can take a mediocre story and put in interesting characters and personalities and have a good show,” Walt said. “We can’t do that in cartoons. We can’t hire actors; we have to create them ourselves. We have to make them interesting, or we’re sunk. I’ve had a lot of fun making live-action pictures, mainly because I can move so fast. But I’ve learned a lot from them. I’ve made mistakes, but now I can apply the lessons to cartoons.”

Another technical crossover was the result of his live-action work. “One thing he may have contributed to the live-action film that isn’t widely recognized is the use of storyboards,” Leonard Maltin says. “Directors today routinely storyboard either their entire films or all their action sequences.

“Hitchcock did that very early on, because he had been an art director and he liked to visualize his films that way—but he was an exception to the rule. Disney, of course, had perfected the storyboard process, first in his short subjects, and then in his animated feature films—but no one had really leaned on that technique for planning out a live-action film until he did.”

In some ways, this method was an efficient way that Walt could maintain the level of creative authority that he demanded. “It was a way that he could conceptualize Treasure Island, for instance, in his studio in Burbank, and then send off his producer Perce Pearce to shoot it in England, with the confidence that it would be the film he expected it to be,” Maltin says. “There was no other way to do that. It was a way of maintaining some control, and having a pretty sound idea of how it would play out—which, of course, is the whole idea of a storyboard: to give you a good sense of the film, not only the story development, but the pace, and the order of scenes, and the way the film flows.

“And apparently, Walt was a master of reading a storyboard, of sensing where something needed punching up, where it was lagging; or where it was too hurried and needed some relaxing. He gave his directors a pretty good blue print. So much so, that I think he felt confident that, if they were competent in any way, he’d get back the film he wanted.”

One might assume that Walt’s creative control was egomaniacal, or abrasive to the directors of the films he produced. But in this era, film was typically a producer’s medium. It was the producer who established the vision and essence of a film production, and oversaw the mixture of all of the elements and talents to create the final film. (This was how Walt had always done animation, and given that Walt maintained a close lifelong relationship with Samuel Goldwyn, one of the fiercest independent producers of all time, the sensibility is hardly surprising.)

“He hired freelance directors,” Maltin explains. “On the one hand, he hired directors who were journeymen—not great masters of the craft, necessarily, but good, competent directors. They didn’t have egos so big, or plans so grand that they wanted to buck Walt, or make ‘their’ version of the film. They were happy to make his film. Yet, when I interviewed several of those men in later years, they said unanimously that they felt great freedom. They felt that they had the ability to go and make the movie, and make decisions, and do the best job they possibly could. I think that’s because they had that blue print. It helped them. It gave them confidence, and Walt stayed out of their way. Walt didn’t try to second-guess them, either on the set, or after the fact.

“Now that might not have been the case had he hired John Ford, or Joseph von Sternberg, or Frank Capra, or any number of other directors who had their own approach, and who bridled at any kind of interference, who resented anybody telling them, or even hinting to them how to do their job. So I think Walt was wise not to hire that kind of director, but to hire somebody who was used to being a journeyman. I think that’s the best word for it. Someone who knew how to do the job, and could do a good job—and would do an even better job, in fact, knowing that somebody gave them a little slack on the reins.”

Although bolstered by the successes achieved with his live-action outings, Walt steadfastly maintained, “As long as I live I’ll always be doing things with cartoons. But I don’t want to be trying to do things with a feature cartoon that could be done better with a good live cast.”

After the British films, a steady slate of live-action production became a staple of Disney for the rest of Walt’s life, and beyond.

These films crossed genres, styles, and conventions: comedy, fantasy, action, adventure, historical drama, serious drama, literary adaptation, documentary, nature films, and even science fiction.

Such varied and still-revered productions as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), Old Yeller (1957), Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1958),The Shaggy Dog (1959), Pollyanna, Swiss Family Robinson (1960) The Absent-Minded Professor (1961), The Parent Trap (1961), The Incredible Journey (1963), Mary Poppins (1964) and That Darn Cat! (1965), were the result of Walt’s own vision of what constituted a “Disney Movie.”

“Hollywood goes along its own way working for formulas,” Walt said, “and we have completely ignored ‘em, and haven’t even tried to be a part of ‘em. We’ve just not cared to try to even compete with ‘em, or think in the same way they do.”

Unfortunately, both for Walt and for the audiences of today, this intensely personal legacy of live-action films is usually derided, dismissed, or otherwise trivialized. No matter the reality of the matter, there is a stereotype of a “Disney Movie” as something insubstantial, childish, or silly—a caricature of a “real” movie.

Unjustly ignored are still-compelling films such as The Great Locomotive Chase (1956), The Light in the Forest (1957), Third Man on the Mountain (1959), The Three Lives of Thomasina (1964), Those Calloways (1965), and Follow Me, Boys! (1966).

Brian Sibley says, “I always remembered Julie Andrews saying to me that when she was approached by Walt Disney to play Mary Poppins, she rang her friend, Carol Burnett, and said, ‘Should I go work for Walt Disney—you know, The Cartoon Man?’ There was still a sense, even in the 1960s, that Walt Disney was ‘The Cartoon Man.’”

Walt himself was frustrated that his live-action films were not more seriously regarded or widely successful. Once, after screening To Kill a Mockingbird, Walt remarked, “That’s the kind of film I’d like to make, but I can’t.”

Walt’s instincts as a total filmmaker left a deep impression on one of the great Disney leading men, Dean Jones. “I had a script that I felt was very good,” the star recalled, “I was pitching it to Walt, and I said, ‘Walt, there’s some great dialogue in this picture,’ and he said, ‘Anybody can write dialogue. What do we see on the screen?’

“He was a movie maker. There were images that moved on the screen and they should be, in his estimation, exciting, and funny, and dramatic—and inthemselves, valuable. So it was very revealing about how he thought about movies…he was interested in the vividness of the moving image over the words that were being said.

“Where Charlie Chaplin designed and built one character and made it famous around the world, here Walt Disney did that with the output of an entire studio, with a whole culture in America.”

In subsequent decades, much effort has been put into creating new “franchises” in Disney live-action output, new Studio management has tried over and over to recapture the past successes by duplicating or remaking vintage Disney live action titles, without even the most basic understanding of what made the films so extraordinary in the first place.

Dean Jones says, “I had met other heads of studios, but they did not imprint their particular view of life, and their particular personal image, onto everything that that studio did. I knew Dore Schary at MGM, Jack L. Warner—these men made all kinds of films, but Walt had a very unique moral view of life—and everything he touched was some part of himself.

“And that was his genius. The genius of being himself.”