“I suppose I’ve always been in love with trains,” Walt wrote, and in October we will celebrate his lifelong locomotive love at The Walt Disney Family Museum, and here on Storyboard. This article about the making of our October Movie of the Month, The Great Locomotive Chase, was written especially for us by Disney Historian Michael Crawford.

One might have thought, in the fall of 1955, that Walt Disney might have had more pressing things to do than visit a film shoot in the remote backwaters of northeastern Georgia. After all, Disneyland had opened only a few months earlier and there was still a studio to run. What project could wrest Walt away from his new wonderland? Perhaps it’s no surprise that the film in question was The Great Locomotive Chase.

One might have thought, in the fall of 1955, that Walt Disney might have had more pressing things to do than visit a film shoot in the remote backwaters of northeastern Georgia. After all, Disneyland had opened only a few months earlier and there was still a studio to run. What project could wrest Walt away from his new wonderland? Perhaps it’s no surprise that the film in question was The Great Locomotive Chase.

The story had been a leading contender for production ever since the Disney Studio began to develop live-action films. It’s easy to see why the story captured Walt’s imagination—it’s a tale of derring-do and a “true-life” historical adventure that takes place almost entirely on speeding locomotives. Disney’s love of trains was already well documented at the time, and was widely remarked on in the press when the film went into production.

Fess Parker, a newly-minted star thanks to his turn as Davy Crockett, was cast as James J. Andrews, the leader of a Union raid that could have dramatically cut short the Civil War. In April of 1862, Andrews led twenty-two men into Georgia where, in full view of Confederate sentries and 4,000 troops, they stole a train while its crew and passengers were eating breakfast. Andrews planned to drive north from Big Shanty (current-day Kennesaw) to Chattanooga, destroying track and trestles as he went, making it impossible for the Rebels to send reinforcements from Atlanta into Tennessee.

What he didn’t count on was intrepid conductor William Fuller, played by Jeffrey Hunter, whose train, the General, Andrews had stolen in Big Shanty. Fuller chased after Andrews for eighty-seven miles, eventually commandeering the steam engine Texas that raced—backwards—until it chased down Andrews near the town of Ringgold. Andrews and his men were rounded up and tried as spies, although some later managed to escape and tell their story. They were among the very first to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

What he didn’t count on was intrepid conductor William Fuller, played by Jeffrey Hunter, whose train, the General, Andrews had stolen in Big Shanty. Fuller chased after Andrews for eighty-seven miles, eventually commandeering the steam engine Texas that raced—backwards—until it chased down Andrews near the town of Ringgold. Andrews and his men were rounded up and tried as spies, although some later managed to escape and tell their story. They were among the very first to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

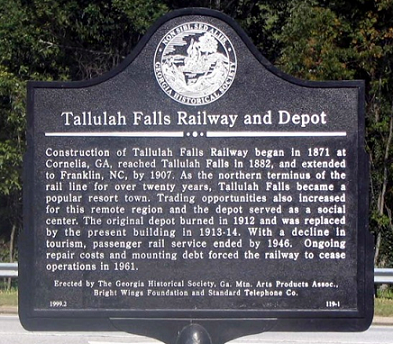

The railroad along which the original events took place continues as a major rail artery to this day, and even by 1955 it had been straightened and modernized so as to be unusable for a period piece. Searching for a suitable substitute for the winding rails of the 19th century, Disney eventually discovered the shortline Tallulah Falls Railroad fifty miles to the east.

The Tallulah Falls Railroad, or “Old TF” in local parlance, seems itself like something out of one of Walt’s rural fantasies. Incorporated in 1897, by 1907 the TF would stretch fifty-eight miles from Cornelia, Georgia to Franklin, North Carolina. The TF opened the isolated area to the outside world, allowing visitors to witness the majesty of the Tallulah Falls (marketed as the “Niagara of the South”).

Eventually the boom-days of the Victorian resorts turned bust, and when Walt arrived in 1955 the TF had been in receivership since 1923. Even spectacular views from the train as it wound a thousand feet above the floor of the Tallulah Gorge couldn’t keep passenger service from ending in 1946, and the TF had hauled only freight since. With only one train running daily, the sleepy little line would make a perfect playground for Walt.

Eventually the boom-days of the Victorian resorts turned bust, and when Walt arrived in 1955 the TF had been in receivership since 1923. Even spectacular views from the train as it wound a thousand feet above the floor of the Tallulah Gorge couldn’t keep passenger service from ending in 1946, and the TF had hauled only freight since. With only one train running daily, the sleepy little line would make a perfect playground for Walt.

The TF was well suited to Disney’s needs. As it wound through the steep Georgia and Carolina hills, the railroad used forty-two trestles in its fifty-eight mile route. All of those, save one, were wooden and of great vintage.

For his steam-driven stars, Walt personally recruited a number of vehicles from the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore. Starring as the General was the William Mason, a 4-4-0 American built in 1856 and still in use today (it appeared as Wanderer in the 1999 featureWild Wild West). Also on loan from Baltimore were the Lafayette, a replica of an 1837 vintage locomotive, as well as two Civil War era coaches, a baggage car, and two ammunition cars.

Another 4-4-0 American, the Inyo, was borrowed from Paramount Pictures to portray theTexas. The vehicles were all shipped by rail to Cornelia, where they were transferred into the care of the Tallulah Falls Railroad. The TF provided engineers and conductors to run the trains during filming—except during breaks, when Walt took the trains out himself. All in all the Inyo and William Mason logged more than a thousand miles during filming—all back and forth over a single thirty-five mile stretch of track.

Filming began in late September 1955, and lasted about six weeks. Casting calls allowed locals to take part in the filming, and many (including the mayor of Clayton) obtained speaking roles. Onlookers watched as hotels were built with fake second floors, and marveled as the Disney crew wrecked boxcars “on purpose.” When the script called for the trains to race into a tunnel, but no tunnels were to be found on the TF, a fake tunnel entrance was built into the side of a hill.

Filming began in late September 1955, and lasted about six weeks. Casting calls allowed locals to take part in the filming, and many (including the mayor of Clayton) obtained speaking roles. Onlookers watched as hotels were built with fake second floors, and marveled as the Disney crew wrecked boxcars “on purpose.” When the script called for the trains to race into a tunnel, but no tunnels were to be found on the TF, a fake tunnel entrance was built into the side of a hill.

Filmmaking took a leisurely pace for locals used to days of hard labor. Actors and extras would gather in the morning in Clayton for costuming and makeup, before taking a bus to the shooting location. Often, they would have to wait for thick mountain mists to lift from the deep valleys before they could begin. Disney provided a huge economic boost for the area, and especially for the men working the TF. They didn’t even have to dress up for filming—although they had to operate the trains lying down, with actors standing overhead. As resident Ernest Anderson recounted decades later in a Foxfire interview, “You ought to have been around when Walt Disney was making that picture up there. He really paid you something. He gave you fifty dollars a week extra, just to buy your Coca-Colas with, outside of your salary; then you got your dinner and supper made.”

Walt himself spent several weeks on set, and was a fixture in the small towns along the route. To this day, local businesses showcase framed pictures of Walt on location, or dining in their establishments. A rumor even persists that he considered purchasing the TF to turn it into a scenic railway, but was dissuaded by its millions of dollars of accumulated debt and back taxes. Nevertheless, the day Disney came to town left its mark on the imaginations of these mountain communities. In the words of Ernest Anderson, “Walt Disney sure was a fellow.”

Michael Crawford is a writer and historian with a lifelong fascination with Walt Disney, his works, and his creative legacy. He is the author of Progress City, U.S.A., a website devoted to uncovering the history of The Walt Disney Company as well as promoting Walt's creative ethos.

The Great Locomotive Chase screens daily through October at 1:00pm and 4:00pm (except Tuesdays, and October 15). Tickets are available at the Reception and Member Service Desk at the Museum, or online by clicking here.

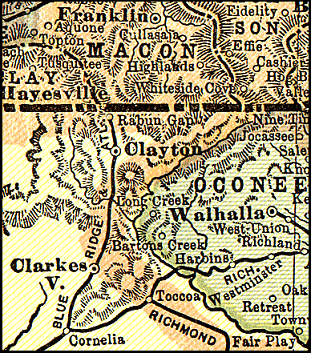

Images above: 1) Walt on location on the Georgia-Carolina border. © Disney. 2) The William Mason, seen here at the B&O Railroad Museum, starred as The General. 3) A 1903 map shows the filming location of the feature. 4) The Tallulah Falls Railroad made its final r un on March 25, 1961.