Disney Legend Mary Blair was one of Walt Disney’s finest stylists—a visualizer of characters and worlds—but her work was not self-contained: it added up to something larger: a story. “Walt responded to the storytelling aspect of her pictures,” historian John Canemaker wrote, “especially the underlying emotion palpable in much of her art, even when veering toward abstraction…. Many paintings are self-portraits of her inner feelings.”

Admired for her rich use of color and form, Blair deserves more credit for her ability to convey the narrative capabilities and applications of her ideas. So, let’s take a closer look at five examples from the archives of The Walt Disney Family Museum…

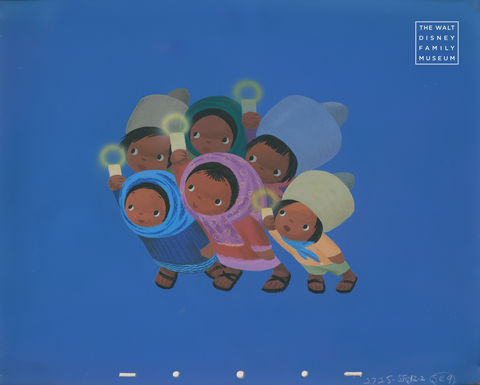

The Children of “Los Posadas”

More than 20 years before the debut of the “it’s a small world” attraction, Blair’s compassion and sensitivity in illustrating the world’s children was evident in her images from research trips to South and Central America. In the vibrant settings of countries including Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Mexico, Blair found the people themselves equally inspiring.

In her work during these travels, she began to develop a signature style of drawing children that “in one way,” as Canemaker put it, “harkened back to traditional American folk art. Her spheroid, sensual, biological forms communicate solace, comfort, joy….” Round-headed with small, innocent eyes, these children made their public debut in the “Los Posadas” sequence from The Three Caballeros (1945), which portrayed a Mexican Christmas tradition whereby children make their way through the town seeking a “posada”—shelter—in the spirit of Mary and Joseph from the Nativity story.

“Los Posadas” is arguably the purest Blair-inspired sequence in any Disney film because her illustrations were directly adapted into the scene with only animation of the flickering candles integrated as subtle accents. “[...] Mary Blair’s color keys were so beautiful,” Disney Legend and artist Ken Anderson later told writer John Culhane, “that Walt thought that an extreme minimum of animation was the candle flickering or the eyes batting… that he could finally capture Mary Blair’s design color and was worth doing, in his opinion, in this manner on the screen.”

This specific illustration from Blair demonstrates not only her adeptness at capturing a child’s innocence, but also her instinct for strong poses that lend themselves to the animation medium. In search of los posadas, the children lean in with hushed anticipation, their expressions hopeful. The simple, blue background conveys the cool, calm stillness of this nighttime ritual, which was likewise incorporated into the final scene.

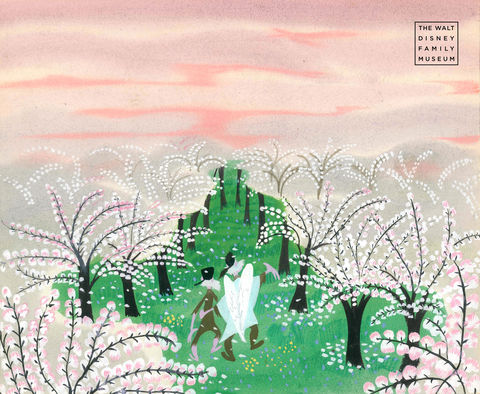

The Fruits of Johnny’s Labors

The “Johnny Appleseed” segment from Melody Time (1948) is commonly (and justifiably) referenced as one of the Disney sequences that took the greatest inspiration from Blair’s visual development. “Appleseed’s” backgrounds often feel like carbon copies of her paintings. “[The] naive, childlike expressiveness actually made it intact to the screen, as far as art direction,” wrote Disney Legend and animator Andreas Deja. “The character styling is still round and dimensional though….”

As Canemaker would note, Walt Disney sometimes struggled to resolve the balance between Blair’s stylings, which were often rendered on a flat, storybook-like plane, with “the familiar rounded/dimensional/realistic Disney style” of animated characters. Disney Legend and animator Marc Davis would add that “this woman was an extraordinary artist who spent most of her life misunderstood. All the men that were there, their design was based on perspective. Mary did things on marvelous flat planes.”

This piece is an example of how Blair’s sensibility can still lend itself to dimensionality. She does it with color. The pinks and whites of the blooming apple trees flow gracefully into the clouds and sunset sky. Johnny’s orchards have become a veritable highway to heaven, and he is joining his angelic friend on the journey there. In the finished film, this blend turns literal when the shot of the orchard dissolves into a heavenly cloudscape and the camera pulls back to reveal the fruits of Johnny’s labors forming a path into the sky. This all begins with Blair’s use of color to convey the emotional moment in the story.

Ichabod’s Encounter with the Headless Horseman

In The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949), nearly five minutes of screen time are used to slowly build suspense as a nerve-wracked Ichabod Crane and his sleepy horse take a moonlit ride through the eerie woods of Sleepy Hollow. Most new audience members likely anticipate what is about to happen and, even still, the Disney storytellers manage to give them a jolt with the appearance of the Headless Horseman.

This rendering by Blair captures the frightfully exciting moment. The Horseman launches into the scene with a flash, arms outstretched in an iconic pose virtually identical to the final animation in the film. Blair has added strokes of pastel—blurring the villain’s form—and conveying both speed and terrific surprise, a technique she employs in other renderings of the character. Ichabod and his horse lurch back in fear, less than half the size of their giant assailant. The gnarled and naked autumn trees seem to make way for the evil spirit, framing the scene.

A notable aside, this depiction seems to place the scene at sunset, rather than midnight as in the ultimate film. The yellow-orange sun is disappearing behind the clouds and shadows fall onto the dusty ground (it might also be a harvest moon). Other renderings by Blair place the scene at night, which align with author Washington Irving’s original description in The Legend of the Sleepy Hollow from 1820.

At the time of her work on Ichabod and Mr. Toad, Blair was a recent transplant to the East Coast, initially following her husband Lee to Maryland where the Navy had posted him during World War II. They later settled on Long Island, a brief drive or train ride from New York’s Hudson River Valley, home to the real-life village of Sleepy Hollow from which Irving had drawn inspiration.

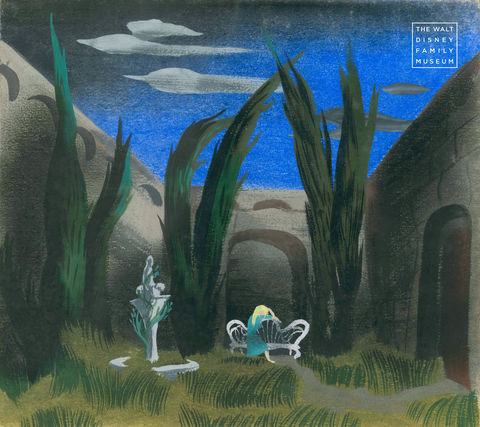

Cinderella’s Heartbreak

No life is without sadness and loss. Blair’s was no different. This piece of the heroine’s despondent cries in Cinderella (1950) is an honest, knowing depiction of sorrow. Cinderella is remarkably small in the scene, the undulating shape of her body blends with the curves of the ornamental white bench. The green grass and trees wave lamentably about her, and high stone walls surround the scene, boxing Cinderella in. She is undoubtedly trapped in this pitiful existence.

But certainty can be dispelled with a change of perspective. Above the stone “prison cell” is a promising sky. A deep, cerulean blue resists encroaching darkness. There is hope yet. Soon the Fairy Godmother will arrive.

Elements of this rendering appear in the final film. The bench becomes a stone slab rather than an ornamental seat. The fountain partly enveloped by a plant is nearly identical, as is Cinderella’s pose. But the Disney layout and background artists elected to place the character within an open garden instead, a weeping willow tree appropriately hanging overhead. Still present is the blue sky, and the wispy, surrounding trees are entirely inspired by Blair’s work.

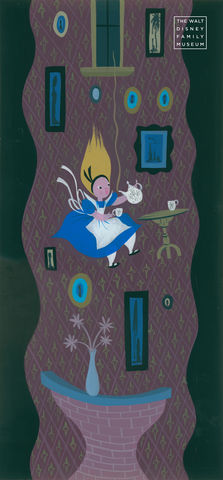

“Down, down, down….”

“Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her and to wonder what was going to happen next.” So writes Lewis Carroll—the pen name of Charles Dodgson—in 1865’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. In all of her stylings for Disney’s 1951 adaptation of the book, Blair infuses Alice with this whimsical curiosity.

But this rendition of Alice’s fall also conveys a sense of space and cinematography. Its vertical composition implies camera direction. The wiggly borders at left and right make for a slightly claustrophobic plunge, although the domestic details—such as the wallpaper and cup of tea—also give the scene a cozy feel. In this image, Blair shows us that Wonderland may be strange, but it is not uninviting.

“There is much more to Mary’s designs than just the surface look, or unique appearance of them,” Disney Legend, artist, and director Wilfred Jackson would write to historian Ross Care. “Contained… within her designs is an expression of Mary’s own response as a sensitive artist, to what the thing is, or the creature, or the person—not just how it looks. Somehow she conveys some of the feeling of what it is like to be the child doing the thing she pictures while that individual child is doing it—or to be the horse, or the owl—or to be the flower, or blade of grass, or cloud in the sky, or whatever the subject she is picturing.

“Mary would respond to this particular aspect of what was to be in the cartoon production in her own way, which was not exactly like the way the rest of us who were working on the cartoon would respond to it,” Jackson continued. “Her styling designs showed her concept of the characters in the cartoon story as well as the locale in which they moved about. And so her styling sketches influenced the ‘look’ of the characters, too. To the extent that the story men and the animators were influenced to feel what it is like to be the person, or owl, or whatever, in the same way Mary felt it—to that [extent], she had a part in ‘designing’ the personalities of the characters in the cartoon as well as the backgrounds.”

–Lucas O. Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

- Mary Blair - Concept Art - Cinderella on bench, Cinderella, 1950; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, From the Estate of Mary Blair; © Disney

- Mary Blair - "Las Posadas" - The Three Caballeros (1945); collection of the Walt Disney Family Museum; © Disney

- Mary Blair - Visual Development - "The Legend of Johnny Appleseed”, Melody Time (1948); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, From the Estate of Mary Blair; © Disney

- Mary Blair - Visual Development – “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

- Mary Blair - Concept Art - Alice falling down the rabbit hole, Alice in Wonderland, 1951; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Diane Disney Miller; © Disney