55 years after its release, The Aristocats remains the first of its kind as a Disney animated feature made without Walt Disney’s comprehensive involvement. But Walt did make some important contributions to the film before his sudden passing in 1966.

“Which pets’ address is the finest in Paris?” sings Maurice Chevalier during the opening of The Aristocats (1970). “Which pets possess the longest pedigree? Which pets get to sleep on velvet mats? Naturellement! The Aristocats!”

The French entertainment icon had previously appeared in two Disney live-action features, In Search of the Castaways (1962) and Monkeys, Go Home! (1967), and his vocal cameo singing The Aristocats’ title song—written by Disney Legends Robert and Richard Sherman—was the 82-year-old’s final film role. It was fitting, considering that Chevalier had grown up in Paris during the Belle Epoque era that provided The Aristocats with its setting.

Chevalier had agreed to interrupt his retirement to record the song as a tribute to his late friend, Walt Disney, who had died at the end of 1966. In a last-minute addendum to that year’s Walt Disney Productions Annual Report, Walt’s elder brother and business partner Roy O. Disney wrote that “it was Walt’s wish that when the time came, he would have built an organization with the creative talents to carry on as he had established and directed it through the years. Today this organization has been built, and we shall carry out that wish.”

Already in development by 1966, The Aristocats became The Walt Disney Studios’ first animated feature produced without Walt’s direct oversight. The film was not without his imprint, however, as Walt had been involved in its surprisingly long and complex gestation.

Production manager Harry Tytle had been with Disney since the mid-1930s when he started as an assistant director. In the early 1960s, Tytle often lived in Europe where he oversaw Disney productions based on the continent. He also assisted with managing story development, and in late 1961, Walt approved Tytle partnering with London-based writer and director Tom McGowan in searching for potential stories to adapt into Disney films.

“When I returned to London shortly after the New Year [1962], I saw Tom, and he had already found stories for consideration,” Tytle would later write in his memoir. “One was a child’s book about a mother cat and her kittens set in New York City. The premise reminded me of our successful cartoon feature about dogs in London, One Hundred and One Dalmatians [released about a year earlier]. I felt the London setting had added an interesting element to the story, and told Tom. Why not a cat story set in Paris?”

It was some time, however, before an animated version of the story was even considered. Throughout its initial development into a story treatment and screenplay, The Aristocats was a live-action film, at various times a two-part television program or a theatrical feature. The story was not dissimilar to what the Disney animation crew ultimately made. The butler (initially it was a pair of butlers) of a well-to-do Parisian woman makes “feeble attempts to eliminate,” as Tytle put it, their employer’s beloved cats, consisting of an elegant Duchess and her brood of distinctive kittens. The felines are first in line for their mistress’ sizable inheritance, and the butler will stop at nothing to take their place. It was all set against the rich backdrop of early 20th century Paris. “The more Tom and I worked on the idea, the more enthusiastic we became,” Tytle wrote.

Tytle lived in Paris himself for a time while developing the story, and soon he and McGowan were joined by writer Tom Rowe, who provided additional contributions. By the late summer of 1962, they had sent a treatment to the studio for consideration, but it was initially rejected. As Tytle would explain, he was convinced at the time that Walt, “the ultimate authority,” had not had a chance to review it himself. It was McGowan who took the initiative, sending the treatment directly to Walt when the studio head was on a trip to London. Walt liked it, and instructed Tytle to prepare it as a live-action feature with McGowan directing.

Story revisions continued through much of 1963 before pre-production was temporarily halted after a disagreement with Rowe about story alterations. It was then that Tytle shifted his view and recommended to Walt that The Aristocats be made as an animated feature. “This could be a benefit to the studio,” he would later write, “as animated features were becoming more and more difficult to come by.” Walt agreed, suggesting Tytle run the idea by Disney Legend Wolfgang “Woolie” Reitherman, who had assumed directorial responsibilities in feature animation. Reitherman’s team was up for it, and The Aristocats joined the lineup of projects. The Sword in the Stone would be released at the end of the year, and The Jungle Book (1967) would start production next.

For Tytle, it was a significant achievement in what was then his nearly 30 years with Disney. He had yearned to make more creative contributions, particularly in animation. By May 1964, not long after Walt and his WED Enterprises team opened four attractions at the 1964—1965 New York World’s Fair, Tytle and writer Otto Englander began active work on this new phase of development. Walt continued to join story meetings as his time allowed, suggesting later that year that “Aristocats should follow the same tack as Dalmatians,” according to Tytle’s recollections. “[Walt] said it would be good if the cats could talk amongst themselves, but never in front of humans.” Among other suggestions at the meeting, Walt also noted that brothers Robert and Richard Sherman ought to contribute songs.

One of Tytle’s most intriguing memories is when studio nurse Hazel George read The Aristocats script and gave a favorable response, “as good to me as a rave in the New York Times,” as the production manager would describe. “Hazel’s taste ran very similar to the movie-going public, a fact not unrecognized by Walt, who often took her opinion under consideration.”

Much was left to be done, however, when Walt suddenly passed away “before the project came to fruition,” as Tytle wrote. With The Jungle Book in its final stretch of production, The Aristocats quickly moved under the direction of the larger feature animation crew. As historian Didier Ghez would explain in his They Drew As They Pleased book series, “Less than two weeks after Walt’s death, on December 28, 1966, director Woolie Reitherman, Disney Legend and art director Ken Anderson, story artists Vance Gerry and Disney Legend Don DaGradi, writer Larry Clemmons, animator Dick Lucas, and executives and Disney Legends Bill Anderson, Winston Hibler, and Bill Walsh met to discuss the future of the feature. They agreed that the story needed to be simplified and the number of characters pared down.”

Ken Anderson had been the only artist to work on The Aristocats before Walt’s death, producing a number of concept sketches after conducting extensive research into both cats and the aesthetics of Paris. The ultimate film had a visual style much akin to One Hundred and One Dalmatians, perhaps in large part due to its near contemporary setting full of modern elements, not to mention the continued use of the Xerox printing process by which penciled animation drawings were copied directly to clear cels before painting.

“There was no replacement for Walt,” Woolie Reitherman would comment years later. “In my view, the main thing was to keep this team together and keep the same creative juices flowing that they had with Walt.” Much of Tytle and McGowan’s story was altered or removed, including, as Tytle himself put it, “the part of the story that most intrigued Walt, that is, adoption into homes befitting the kittens’ talents….” Disney Legend and animator Ollie Johnston would recall that “we all worked hard to help [Woolie], but The Aristocats was a tough picture to make. It wasn't a real cartoon story. It was a live-action story, full of live-action characters.

There were, however, some key elements to The Aristocats that—thanks to Walt’s own influence—had become increasingly prevalent in Disney animated features. One was its largely original story. “We do much better with our own stories where we have greater latitude,” Walt said in 1965, during which time The Jungle Book was undergoing major story changes that moved the film increasingly further away from its source material. After years of adapting novels, short stories, fairy tales, and myths, Walt had steadily grown the Studios’ capacity to develop their own stories in both live-action and animation.

Another of Walt’s influences was the use of animals as main characters. This aspect, of course, had the deepest of roots in Walt’s 40-odd years of storytelling, but there was a noticeable swing towards animal-based stories in the decade leading up to The Aristocats with Lady and the Tramp (1955), One Hundred and One Dalmatians, and The Jungle Book. These tales harkened back to the studio’s earliest successes with the personification of mice, ducks, and dogs—among many others—as believable, entertaining characters. This had both literal and figurative implications for the emotional dynamic of a story. TIME magazine took notice in their review of The Jungle Book, writing of how “the reasons for its success lie in Disney’s own unfettered animal spirits, his ability to be childlike without being childish.”

The Aristocats again took a strong lead from The Jungle Book in its voice casting. Phil Harris, who hadd led The Jungle Book's cast of animals as the voice of Baloo the bear, would again take a leading role in The Aristocats as Thomas O'Malley. Walt had been the one to suggest Harris, by then a celebrated entertainer, for the role in The Jungle Book. After Aristocats, Harris would again take a lead role as Little John in the subsequent Disney release, Robin Hood (1973), another example of Walt's influence stretching deep into the future after his own passing.

The Aristocats arrived in theaters 55 years ago on Christmas Eve 1970. It was the 20th Disney animated feature, the first largely made without Walt’s involvement during active production, and the only one made under the direct auspices of Roy O. Disney, who passed away a year later. It garnered enough success to greenlight Robin Hood, and perhaps even more importantly, as historian Leonard Maltin would put it, “set the wheels in motion so as not only to continue the Animation Department, but find a way to keep it healthy and growing.” A major contributor to that continuation was the California Institute of the Arts, a school that before his passing Walt had helped establish, and which formally opened its doors in 1970.

The Aristocats was a critical achievement on behalf of the animation team—the artists who had worked with Walt longer than anyone else. As historian Michael Barrier would observe, in spite of its story challenges, “the level of craftsmanship remained stubbornly high.” With this dedication to Walt’s own creative principles, the animation team was determined to endure. As assistant director Danny Alguire would remember of the time, “Our ‘pillar of strength’ was gone. The burden fell on Woolie Reitherman…. No one heard him say what was on everyone else’s mind, ‘Can we do it without Walt?’ We did it. We moved right into production.”

—Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

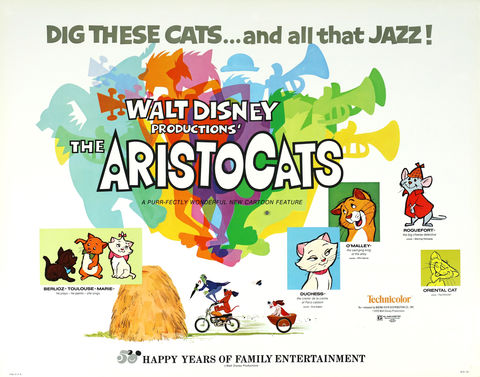

- Half sheet poster - The Aristocats (1970), 1973 rerelease; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Dean Barickman; © Disney

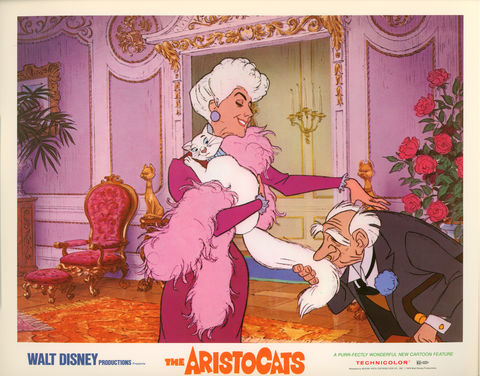

- Lobby card - The Aristocats (1970); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Dean Barickman; © Disney

- Photograph - Disney animators (L-R: Milt Kahl, Ollie Johnston, John Lounsbery, Frank Thomas, Woolie Reitherman) in studio, laughing, October 1, 1967; Collections of the Walt Disney Archives and the Walt Disney Family Foundation, Ollie Johnston Collection; © Disney

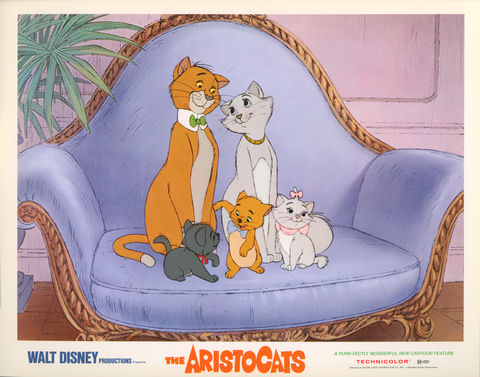

- Lobby card - The Aristocats (1970); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Dean Barickman; © Disney