To those who knew her, and to those of us today who can only learn about her, Mary Blair was a remarkably compassionate woman. “There’s a story about Mary going to Walt Disney with a request,” recalls Maggie Richardson, one of Blair’s nieces. “They’d built ‘“it’s a small world”’ and were getting ready to ship it to New York to be reassembled at the [1964-65 New York] World’s Fair. Mary explained to Walt that there were a lot of people in California who were involved in getting this together on a very severe timeline—could they also come to the Fair?

“She was like Norma Rae,” Richardson adds in reference to the 1979 film starring Sally Field. “She got the people out to the Fair, and when they arrived, she took them out on the family boat at King’s Point on Long Island, which was her greatest joy.”

Today the steward of her aunt’s legacy and estate, Richardson was recently at The Walt Disney Family Museum to participate in a live discussion with historian and author John Canemaker, who has conducted more research and published more writings about Blair than anyone else to date. The pair sat together for a conversation about Blair before joining their audience in the museum theater.

Canemaker reflects, “I wish I had known her,” but admits, “In a way, I feel that I do.” He shares another example of Blair’s compassionate heart, involving a young boy, Neal, at the time a childhood friend of Mary and Lee Blair’s son, Donovan. “He used to see the family at their home on Long Island,” the historian explains. “They’d go out on the boat. Neal loved The Three Stooges; he was crazy about them. Mary was on one of her cross-country plane trips for a meeting in California, and on the plane was Moe Howard, one of The Three Stooges. Mary went up to him and explained that she had a young friend who was one of his biggest fans, and would he sign an autograph for him?”

“That was so typical of Mary,” Richardson says. “She was one of the kindest, most thoughtful people ever.”

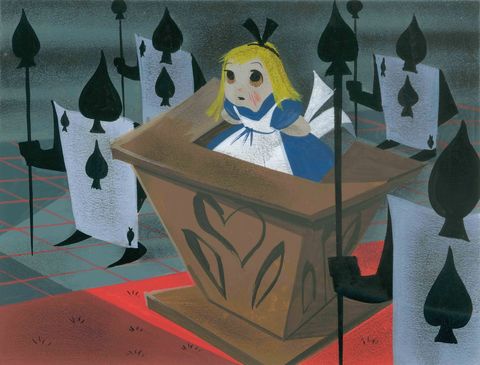

Blair’s sensitivity was imbued in her artwork, not least of all the many color stylings and inspirational sketches made for Disney productions. “She had great sympathy, even for a very self-possessed character like Alice [in 1951’s Alice in Wonderland],” says Canemaker. “Mary was able to find moments within her concept drawings of Alice that have feelings of sadness or fear.

“Particularly with Cinderella as well,” Canemaker goes on to say about the 1950 animated feature of the same name. “There’s a wonderful picture of Cinderella looking into a gilded mirror, and she’s trying to make herself look just as regal in her tattered dress. She puts a little rose in her hair. It tells so much. There’s another picture of Cinderella up in the attic, inside a cold room with low ceilings, and she’s looking out the window. You only see her from the back. When you show a character from the back, that’s the most vulnerable thing. The castle is there, out the window. Maybe she’s thinking, ‘I’ll never get any closer….’”

Richardson draws a comparison to another memorable Disney concept artist, Eyvind Earle, best known for styling the 1959 classic, Sleeping Beauty. Earle, as she explains, had been sickly as a child, and grew up in a relatively isolated manner. His paintings, Richardson observes, are often absent of people, or populated by lone figures. Blair’s human figures, however, “are usually interacting with others or moving in some way. It was a different approach. There might not even be a lot of detail in a person, with just a blob for a face, but you know they are a person with feelings, just with a few strokes.”

Complementing this sense of empathy is Blair’s use of color and abstract shapes, as Canemaker notes. “A lot of her work looks like collage. That exploded when she did ‘“it’s a small world”,’ but you also see it in so many of the concepts for Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, and Peter Pan [1953].”

Known to be generally modest and quiet herself, Blair was no less sympathetic and receptive to the world around her. The artist’s natural curiosity was fueled by an education that never ceased, first at San José State University and the Chouinard Art Institute, and continuing through her mature career with ongoing research. “She was always learning,” as Richardson says.

“I once found a book on paper sculpture that she had,” Blair’s niece continues. “She designed a window display for Bonwit Teller in New York, for which she sculpted paper. At another time, she bought a book on early American quilts for her research on So Dear to My Heart [1949]. You can see that she worked those influences into her designs. Later, she ended up with a kiln in their home near Santa Cruz, and she made ceramics. They had a real ‘Mary Blair’ style, simplistic and different.”

Canemaker explains that “Mary had great respect for research, looking at what was real and using it as a jumping-off point to incorporate her own style. It had to start with the real, which is the same thing Walt Disney said, ‘If you don’t know the real, how can you do the surreal?’ Both Walt and Mary had a great respect for learning.” The historian further adds that “Mary took it from the culture as well. She took inspiration from advertisements and posters, especially from Europe. She looked at the colors people were using and adapted them to her own style. It was a continual learning experience throughout her career.”

Together, Richardson and Canemaker—along with Richardson’s late sister Jeanne Chamberlain and Blair’s own late children, Kevin and Donovan—have done more than anyone to foster Mary Blair’s legacy. The effort began decades ago with the publication of Canemaker’s first books covering the artist and the ongoing effort by the family to showcase Blair’s personal artwork and elucidate her life story. Nearly 50 years since her passing, Mary Blair is as popular and appealing as ever. “I’m always amazed by it,” Richardson comments. “Mary would have been so touched and surprised, in a way. She was certainly aware of her own talent, but she was still pretty humble.

“A few years ago, I got a call from a woman here in Northern California, and her nine-year-old daughter was giving a book report on Mary Blair,” Richardson continues. “She asked if her daughter might interview me. Her name was Elizabeth, and she had all of these intelligent questions about Mary. They later sent me a picture of the costume they made with Mary’s Imagineering helmet and everything. I’ve met a number of parents who have children who respond to Mary’s art. It’s timeless.”

Canemaker laments the fact that Blair herself did not live to receive public adulation, especially when considering that—near the end of her life—Blair periodically faced prejudice and criticism for what some described as her “passé” style. “But Mary’s endurance is certainly well-deserved,” he asserts. “Quality will out. People appreciate her work and are amazed at the beauty, cleverness, creativity, and her fecundity and generosity with it all. She was so full of creativity. It’s amazing what has happened in just the last 10 years. It’s only going to grow.”

The late Diane Disney Miller and The Walt Disney Family Museum have helped play a central role in this continuing Blair renaissance. Miller's personal respect for the audience stretched into her own childhood. As Richardson notes, “Mary had been over to the Disney house for dinner many times. Diane and Sharon had really admired Mary when they were kids.”

A core element of Miller’s vision for the museum was not only to present the in-depth story of her father’s life, but also those of the artists who worked alongside him. Blair became one of the first individuals to be honored with a special exhibition of her own, in 2014. “Diane had an idea and she went for it,” Canemaker says. “Like her father, she had that determination. I remember having meetings here—probably for the original Mary Blair exhibition—and we’d joke and kid around at first, then the meeting would begin and you’d get that ‘Disney eye’ as she looked at you with focus and intent. You thought, ‘Oh my goodness, this better be good!’ [laughs]”

Canemaker describes his own journey chronicling the lives of artists like Blair as “a dream,” adding that Miller was “a real pollinator of projects, and the people here at the museum now are continuing that legacy.”

To support Mary's ongoing legacy, visit Magic of Mary Blair or connect via Instagram.

—Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

- Photograph - Mary Blair on dock; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Jeanne Chamberlain and Maggie Richardson

- Visual development art - Alice in the witness box - Alice in Wonderland (1951), c. 1950; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

- Visual development art - Cinderella looking at castle, Cinderella, 1950; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, from the Estate of Mary Blair; © Disney

- Photograph - Mary Blair portrait; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Jeanne Chamberlain and Maggie Richardson

- Photograph - Mary Blair in front of "it's a small world", c. 1966; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Jeanne Chamberlain and Maggie Richardson; "it's a small world" used by permission from Disney Enterprises, Inc.