As Disneyland celebrates its 70th anniversary this year, there is still plenty to learn about how the Walt’s original park was created. Historian and retired Disney Imagineer Tom Morris has been on the frontlines of this research, and his forthcoming book—Walt Disney Imagineering: In the Beginning 1952–1955 from the Hyperion Historical Alliance Press—helps us to take a more nuanced look at how Walt Disney arranged the ideal team to construct his dream park.

Visitors perusing the main galleries at The Walt Disney Family Museum encounter dozens of quotations from the institution’s namesake emblazoned on the exhibit walls. As they reach the marvelous climax that is Gallery 9—with its Lilly Belle train, Disneyland miniature, and countless other treasures—the largest such quote of them all is visible on the right-hand wall.

“You can dream, create, design, and build the most wonderful place in the world,” Walt said, “but it requires people to make that dream a reality.” Who were those people?

An oft-repeated story of Disneyland’s origins tells of the so-called “lost weekend” in 1953 when Walt and conceptual artist Herbert Ryman worked closely together to create the first bird’s eye view rendering of the Park. This was then used by Roy O. Disney as a proof-of-concept to help secure initial funding. But what is lesser known is that Walt and Ryman weren’t on their own that fabled weekend. A handful of the earliest Imagineers—though they were not known by that moniker yet—had been working closely with Walt to flesh out the park concept before Ryman started his illustration.

“Story sessions were held prior to Herbie’s work on the park rendering, which needs to be clarified in the historical record,” Morris explains. “Herb Ryman was not alone with Walt that weekend. Marvin Davis, Dick Irvine, and, I believe, Dave Bradley, were on hand to provide input when needed. And even before Herbie had been called in, they’d already determined what was going to be in the pitch given by Roy Disney the following week. So they wrote a description of each land with the attractions. Some sketches had already been done by Bruce Bushman, Bill Martin, and Marvin Davis. Davis had already done a schematic layout of the park and drawn a proposal for the castle pretty close to how it looks today. A lot of the content was there for Herbie to extrapolate from, which is probably one of the reasons why he was able to [work] it out so beautifully in just two days.”

“You’ve got to have your own people.”

Another historical detail concerns where the core group of Disneyland’s original designers came from. In the early 1950s, The Walt Disney Studios’ existing artists worked primarily in animation, with some live-action productions being made overseas. But these artists were not recruited by Walt to design his new park, at least not initially.

When WED Enterprises was formed in 1952, there was no backlot sets at the Disney Studios in Burbank. Disney had yet to make a fully live-action feature in Hollywood. 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) would soon become the first, but Disneyland’s early development ran in parallel with much of that film’s production. So where did Walt find these early park designers like Dick Irvine and Marvin Davis? From the other major studios in Hollywood.

“I think that there was an agreement in the contract between Walt and the studio, when they allowed him to start WED,” Morris says, “that Walt was not to cannibalize the talent at the studio because they had important and expensive groundbreaking projects taking place. They had to finish Peter Pan [1953], then 20,000 Leagues [1954], and Lady and the Tramp [1955], [the latter two of] which were both in CinemaScope.”

As Morris further explains, Walt had been consulting with architects William Pereira and Welton Beckett and amusement park entrepreneur Dave Bradley about how best to create a physical place, something Walt had never done in an artistic context before. “They gave Walt advice about starting up his own team to maintain his own control before he handed the designs over to the architects. Walt needed his own people, and that’s where that all started in early 1953. The objective was to get started on the right track in the real world. You can dream and come up with all sorts of crazy stuff, but if it isn’t informed in some kind of reality, you’re going to spend a lot of money redesigning everything later on.”

Fox, MGM, and Warner Brothers

“Actually, the first job for WED wasn’t Disneyland, it was Zorro,” as Morris says. Television and the park were intertwined from the earliest stages. Initially, Walt determined that producing an episodic Zorro series would help generate revenue for Disneyland’s construction. WED’s first two employees Nat Winecoff and Bill Cottrell began script development, and by the spring of 1953, art directors Dick Irvine and Marvin Davis were hired from 20th Century Fox—presumably to lead production design on the series. “Walt already knew Irvine because he’d worked on Victory Through Air Power [1943] and The Three Caballeros [1945],” as Morris adds.

But soon after Irvine and Davis were hired, the original Zorro deal fell through due to projected high costs—the series would not be made ultimately until later in the decade. Still eager to get moving with Disneyland, Walt already had two art directors on staff, so he quickly put them to work on the Park instead. “Walt had earlier established a livestock corral on the studio lot and were also making stagecoaches in anticipation for the Park,” Morris says. “People were spending Walt’s money, so it was time to get started on Disneyland for real.”

Soon, an increasing number of film production artists were recruited from Fox in addition to MGM. Art director Harper Goff was busy starting work on 20,000 Leagues with another group recruited from his former employer, Warner Bros., where Goff had worked as a set designer. Many of them would eventually come over to WED. Bruce Bushman soon became one of the first preexisting Disney Studios artists to work on Disneyland. (Earlier on, both Goff and studio artist Ken Anderson had worked on precursor ideas for miniature sets and automata that later informed the ultimate Disneyland concept.)

“At some point they realized that there was mutually beneficial talent swapping they could do between WED and the studio,” Morris explains. “When 20,000 Leagues wrapped, John Hench became available, for example. There was a period of inactivity following that production, and he didn’t immediately have anything to do, so Walt moved him over to WED for a time, though he wasn’t an official employee until years later. John, Claude Coats, Ken Anderson, and several others were ‘loaners’ in those earlier years. When Lady and the Tramp wrapped, Sleeping Beauty wasn’t ready for them to start yet, so Claude and several others from his unit became available, and that’s when they did Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride and the other dark rides.”

The Hollywood artists hired over to WED were mostly industry veterans with decades of experience working on hundreds of films in every conceivable genre. Many were trained and licensed architects—some with experience studying at European universities—who had been driven into the film industry during the Great Depression. They could build anything and make it look appealing, which became essential for Disneyland’s mix of styles and historical periods.

The Prospectus

The Walt Disney Family Museum’s archive holds a copy of Disneyland’s original prospectus, created in 1953 by Walt and the early WED staff ahead of the fabled map illustration by Herbert Ryman. “Like Alice stepping Through the Looking Glass, to step through the portals of Disneyland will be like entering another world,” declared its introductory lines. “Within a few steps the visitor will find himself in a small midwestern town at the turn of the century.” The succeeding overview details much of what became the physical park a couple years later, with a few interesting omissions.

As described in the prospectus, Main Street had its Emporium “where you can buy almost anything and everything unusual.” True-Life Adventureland featured an explorer’s boat trip and a botanical garden with live birds and fish—themselves available for purchase. The World of Tomorrow previewed a futuristic “monorail train;” the “Little Parkway system,” a forerunner of the Autopia; and a studio where a planned television show would be produced. Fantasy Land had its castle, carousel, and Peter Pan attraction (the animated film was released in tandem with this early development work). Frontier Country was “where the stagecoach meets the train and the riverboat for its trip down the river to New Orleans.”

There was also Holiday Land for seasonal festivals, Recreation Land with its “shady park” available for private rentals, and Lilliputian Land—“a land of little things” that later evolved into the Storybook Land Canal Boats.

“Disneyland will be the essence of America as we know it,” the prospectus declared, “the nostalgia of the past, with exciting glimpses into the future. It will give meaning to the pleasure of the children—and pleasure to the experience of adults…. It will focus a new interest upon Southern California through the mediums of television and other exploitation…. It will be a place for California to be at home, to bring its guests, to demonstrate its faith in the future… And, mostly… it will be a place for people to find happiness and knowledge.”

Making Magic, And Fast

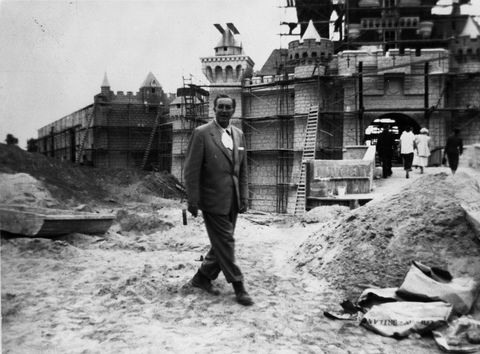

By the end of August 1954, vertical construction had begun on the Disneyland property in Anaheim. “These guys hit the ground running,” Morris says. “Because they had done dozens of films, they had an incredible sense of things like shape language and scene blocking. Disneyland was playing off of the popular film genres of the time. People were interested in the subject matter of these different realms. Live-action film designers from the various studios could do this in their sleep. It didn’t take much coaxing or training. They just slammed it out.

“A good example of that is Main Street,” Morris continues, “which was done in a phenomenally short period of time and in some respects is the most complicated, at least architecturally. You have a lot of ornamental milling that has to go together. You have windows, sashes, and doorways that all have to fit, otherwise you’re going to have issues like rain intrusion and other problems down the road. It has to look authentically beautiful but also last over time and be built to code. I’ve witnessed on other projects how long it takes to get something like Main Street through construction drawings. Main Street at Disneyland was done in a very short time, and that only could’ve been done by people who had done it before—time and again.”

Morris notes candidly that many of these film production artists “were ‘talented hacks’ in the best sense,” as he puts it. There may have even been a sense of reluctance from some of those approaching their sixties and nearing retirement. Due to the other studios downsizing, many went to work on Disneyland because the studio was willing to take them in, and in some cases, bridge their time. It’s important to recall that few anticipated the iconic status that Disneyland would ultimately attain in popular culture. “There was probably some grumbling from some of these guys,” Morris notes. “They’d brought [The] Wizard of Oz to life and all of these great pictures, and now they’re working on a ‘carnival,’ from their viewpoint.”

Whether they appreciated the vision of Disneyland or not, the skills of these artists had everything to do with Disneyland’s success at engaging its audience. “They knew where to put landscaping in relation to a building,” Morris explains. “They knew how to give buildings a lyrical quality so that they looked real but also had a sense of film fantasy. Film strives for realism but with a little tweak that makes it cinematic. That’s what these artists had: an ability to arrange buildings and scenes in a way that they knew would resonate with the public. There wasn’t much thinking about it; there was no time to think.”

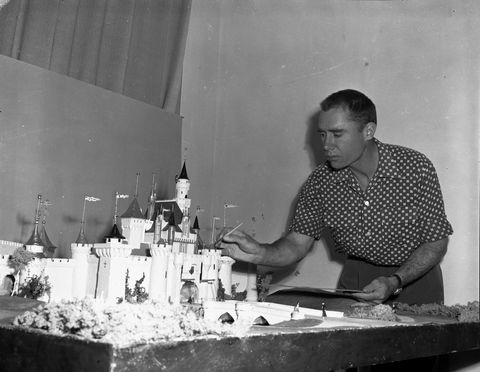

At the end of Main Street, U.S.A. was Disneyland’s castle, eventually named for Sleeping Beauty, whose Disney film adaptation was still years away. According to Morris, it had been the focal point for the park since at least the late summer of 1953, designed primarily by Marvin Davis and Roland Hill with additional suggestions by Herb Ryman.

“I love the quality of the Disneyland castle,” observes Morris. “A lot of it had to do with the availability of backlot craftsmanship. Each of the studios had a plaster department, what you called a ‘staff shop.’ These [teams] knew how to do every kind of facade and it was a craft that was handed down over time. That was the vernacular that they used. Maybe because it had to read on film, things had a little bit more texture. There’s strong contrast between molding and surface area and trim.

“A lot of the exterior backlot design mentality came from what they learned from cinematography,” Morris continues. “That’s why backlot streets twist and turn. You get more value out of it. You can switch angles and things like that. That kind of knowledge was brought over to building Disneyland. I almost suspect that there might be a castle similar to Disneyland’s, in some old film, just as you can trace “elements of Pirates of the Caribbean to a particular film. Almost everything back then had a motion picture origin they could use as a starting point.”

Growing Out of Cinema

Since Disneyland first opened, it has been generally understood that Walt Disney translated his experience and skills as a filmmaker into a new medium of fully-dimensional entertainment, the theme park. But Morris’ new research brings the nuance of this translation into much sharper focus. It was, in fact, the fast-paced, visually-inclined skills of film production artists—most of whom had not previously worked for Disney—who contributed so much to the park’s uniqueness. And as importantly at the time, they managed to do it on a rapid-fire schedule akin to a typical film’s, helping Walt open the park as quickly as possible before finances were drained.

Though Disneyland has changed significantly these last 70 years, much of the original work created by the artists in 1954 and 1955 remains—from Main Street, U.S.A.’s ornamental architecture to Sleeping Beauty Castle’s iconic silhouette. Their foundational artistry remains at the heart of The Happiest Place on Earth.

–Lucas O. Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

- Walt Disney and Richard Irvine in front of the reconstruction of Canal Boats of the World into Storybook Land Canal Boats, c. 1956; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives; © Disney

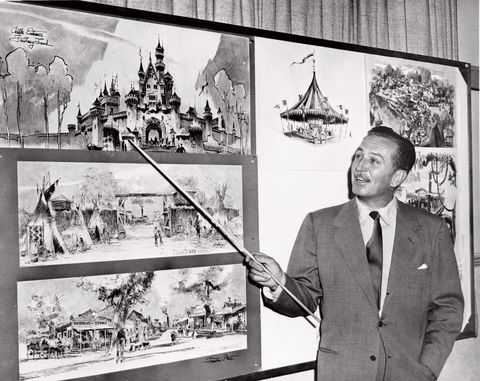

- Photograph - Walt showing Disneyland concept art, c. 1955; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

- Photograph – Eyvind Earle painting a model of Sleeping Beauty Castle, c. 1954; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives; © Disney

- Photograph – Walt Disney walking in front of Sleeping Beauty Castle during construction of Disneyland park, 1955; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives; © Disney