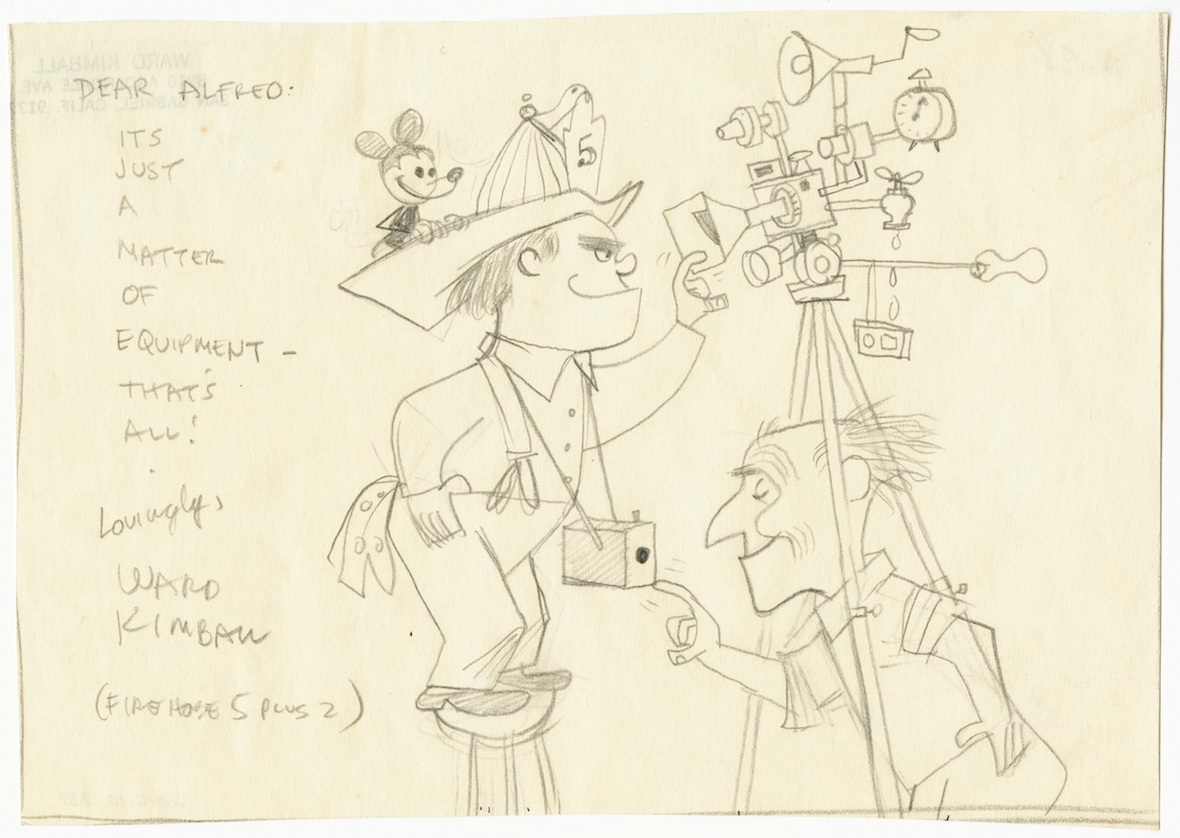

For 22 years, there existed a band that gained worldwide fame whilst always maintaining “regular” jobs on the side: the Firehouse Five Plus Two played Dixieland Jazz for the fun of it. On weekends and weeknights, they threw off their daytime attire of Disney Studios artists, donned white fire helmets with full red and blue garb, and exploded onto the stage. Their Chief and first trombonist was animator Ward Kimball, for whom we are currently celebrating his centennial year.

Early in his life, Ward Kimball demonstrated an aptitude for music. Before joining The Walt Disney Studios in 1934, he played trombone for such outfits as the Santa Barbara Symphony. Conditions at an animation studio could be quite intense with close quarters, heat, and intricate drawing tasks all adding to the pressure. But come lunch hour, the halls of the animation building would echo with music, as Ward—along with many others including Frank Thomas and Harper Goff—would let loose in the joy of jazz music.

Early in his life, Ward Kimball demonstrated an aptitude for music. Before joining The Walt Disney Studios in 1934, he played trombone for such outfits as the Santa Barbara Symphony. Conditions at an animation studio could be quite intense with close quarters, heat, and intricate drawing tasks all adding to the pressure. But come lunch hour, the halls of the animation building would echo with music, as Ward—along with many others including Frank Thomas and Harper Goff—would let loose in the joy of jazz music.

These lunch hour jam sessions extended to weekend celebrations at the Kimball home. Eventually, the group began performing for parties at the Studios and other local functions. Throughout the 1940s, with Ward as leader, they were known by a variety of names, including the Huggajeedy 8.

In 1954, Groucho Marx asked Ward Kimball, a guest on his television program You Bet Your Life, why the band was called the Firehouse Five Plus Two. Ward coyly responded, “Because there’s seven of us.”

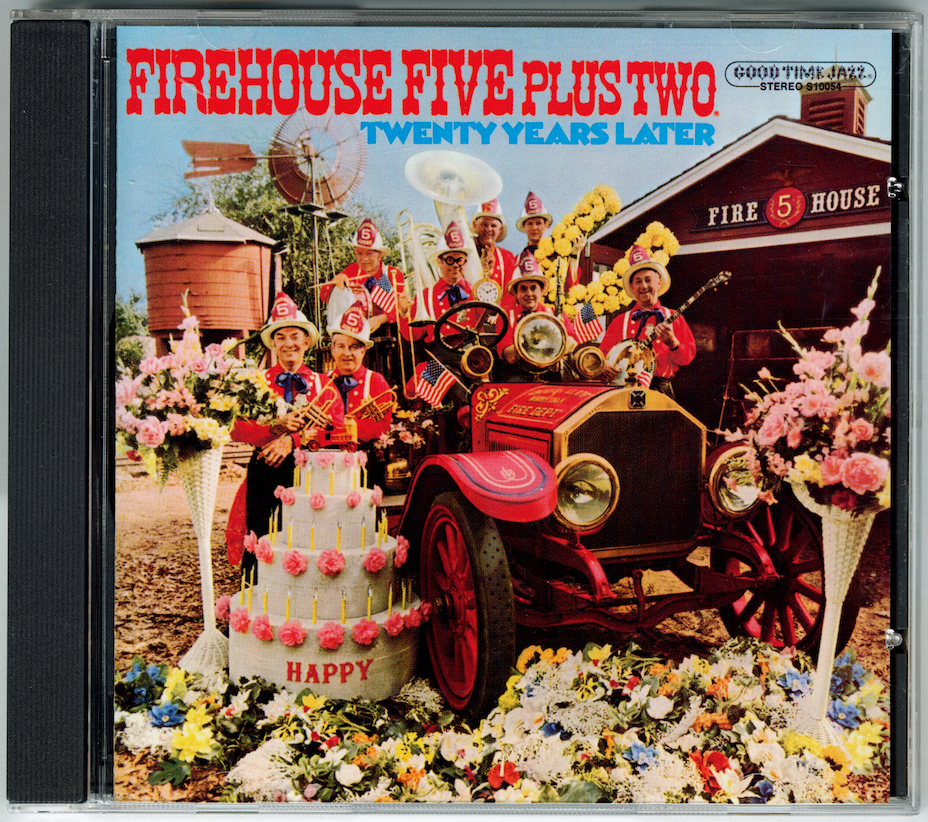

Collection Walt Disney Family Foundation, © 1953 Disney." />By 1948, the band had indeed evolved into a seven-piece ensemble. That year, Ward and his wife Betty agreed that the band should join along on the Horseless Carriage Club Caravan from Los Angeles to San Diego. As Ward would be driving his antique fire engine—with the band piled in behind wearing fire suits and helmets—the theme was set. The Firehouse Five Plus Two were born.

Collection Walt Disney Family Foundation, © 1953 Disney." />By 1948, the band had indeed evolved into a seven-piece ensemble. That year, Ward and his wife Betty agreed that the band should join along on the Horseless Carriage Club Caravan from Los Angeles to San Diego. As Ward would be driving his antique fire engine—with the band piled in behind wearing fire suits and helmets—the theme was set. The Firehouse Five Plus Two were born.

A new theme proved the catalyst with which to make the band famous. They added characteristic signatures by wailing sirens and clanging bells during songs. Ward, the chief, would blow his whistle to call order. Producer Lester Koenig described, “Not having to play for money, they were free to do what they liked. They liked jazz, liked to play it, and played to please themselves.” They were driven by passion, and above all else: a sense for fun.

In musical context, they were part of the West Coast Dixieland Revival, a renaissance of traditional jazz in California, focused originally in San Francisco in the 1940s. The band had their own unique sound within that canon, featuring an unusually democratic representation of the instruments, with each man taking his turn with a solo. Above all, they played fast, very fast. Their tempo at times could be beyond reason, but always driven by fun and highly encouraging to dancing.

The group always remained a part time affair—never conflicting with their work at the Studios and keeping the playing as fun as possible. In the early years, they headlined famous clubs such as “The Mocambo” on the Sunset Strip in Hollywood. But their usual bills over the years were lower-keyed gigs, parties, reunions, fairs, and dance halls, all within reasonable distance in California and Nevada. Twice a year, the band made jaunts north to San Francisco to play at the legendary Earthquake McGoon’s, home of trombonist Turk Murphy and his jazz band. They also appeared on a variety of television programs, including The Mickey Mouse Club, and were regular guests at Disneyland (releasing a live album from the Golden Horseshoe Saloon). The likes of Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Bing Crosby all joined the band on stage. As the band grew in fame, people asked Walt Disney if he worried whether they would move full time into music. He’d respond, “I think what they’re doing is swell. It’s not only good for them, but it’s good for their work at the studio.”

During the span of more than two decades of fun, they had released 12 albums and turned down millions of dollars worth of bookings. Ward Kimball remained the one consistent member of the group as others came and went over time. The band was always a unit; acting together and performing together till the end. They finally hung up their helmets for the last time in 1971 after their final gig at the Anaheim Convention Center near Disneyland. New York Times critic John S. Wilson would describe the band aptly: “It is just happy—an enviable condition for anything.”

During the span of more than two decades of fun, they had released 12 albums and turned down millions of dollars worth of bookings. Ward Kimball remained the one consistent member of the group as others came and went over time. The band was always a unit; acting together and performing together till the end. They finally hung up their helmets for the last time in 1971 after their final gig at the Anaheim Convention Center near Disneyland. New York Times critic John S. Wilson would describe the band aptly: “It is just happy—an enviable condition for anything.”

In the music and zest of the band we see personified the spirit of those like Ward with an insatiable love of life and a good time. They stand today as more than just a band, but a testament to fun, passion, and good music.

Lucas O. Seastrom served as a volunteer for two years before joining the staff as a Museum Educator in late 2014. He is a writer, filmmaker, and historian. His Disney studies can be found here.

Sources

-Canemaker, John. "Ward Kimball." Walt Disney's Nine Old Men and the Art of Animation. New York: Disney Editions, 2001. 80-123. Print.

-Firehouse Five Plus Two. Firehouse Five Plus Two Goes to a Fire! Lester Koenig, 1964. Vinyl recording.

-Sampson, Wade. "The Secret Origin of the Firehouse Five Plus Two." Mouse Planet. N.p., 13 May 2009. Web.